Splendor and Squalor: PART I

6:00 am

Nazinga Game Ranch

Burkina Faso, West Africa

The sun has been up for some time but if I hadn’t been up since before 5 o’clock to see it rise, I’d never have known it. I’m sitting precariously on the roof of a Toyota Land Cruiser, fingers braided awkwardly through the latticework of the vehicle's luggage rack, watching the vast African horizon buck and swell with every uneven inch the truck consumes. The deep green of the bush appears in muted tones beneath a sky as black as pitch. Sinister clouds--heaving things that move as if alive and seem low enough to glide your fingers across--dominate the heavens. We’ve barely left our camp and already it looks as if the heavens are going to be rent asunder.

Atop the car beside me sit my mother and a young Dutch couple. My mother’s hair blows in the ozone-laden wind and her eyes gleam with child-like pleasure. I know she loves this sort of thing. While Karin seems content to curl her legs beneath her, Indian-style, her husband, Robert, with legs longer than spears, appears utterly uncomfortable. Ultimately he throws his legs over the side, opting to sit sidesaddle.

It has been only fifteen minutes since we left our warm cups of Nescafe instant coffee behind in the ranch mess-hall and already the punishing road—rocky, pitted with gaping holes, and sodden with deep pools of brown water—is giving us menacing previews of what our backsides are going to feel like come day’s end. If it weren’t for the sheer pleasure of the experience, we might all think it perfectly absurd that we’re clinging for dear life atop the roof of a moving SUV while its cavernous interior cradles only two occupants. At the wheel is our African driver, who comes included with the truck’s rental package. Sitting shotgun is Clark Lungren. A Canadian whose parents were missionaries, Clark grew up in Africa and has never left. The Nazinga game ranch we now explore is his creation—the largest, most densely populated one of its kind in West Africa. For the last 20 some years, Clark and those he’s trained have sought to strike a delicate balance between the needs of the human population and the necessity to protect the land and its animal inhabitants from human predators. Through a wise mixture of limited game cropping, local employment, eco-tourism and anti-poaching measures, Nazinga has become such a success that the government of Burkina Faso recently wrested control away from its founders so that it might benefit from the reserve’s bounty and prestige. These are all issues, we have learned, that Clark is more than ready to discuss ad-nauseam.

Listing hard to the left, my body tenses as I prepare to leap off should the Land Cruiser overturn. “You ever roll one of these?” I yell to Chuck as we right ourselves, surging from a frothing sea of mud. “Never,” he shouts back. His reply gives me some solace. Still, there’s a first time for everything.

There isn’t much talk. Most of the time its strained whispers, half-snatched away by the wind, which make up our conversation. We’re all too busy to talk, nor do we want to make the noise. We keep our faces shoved firmly in binoculars, our eyes darting across the landscape for any signs of life. The ranch abounds with animal activity although our arrival in the rainy season severely limits what we might view. Trees heavy with thick leaves, foliage in deep bloom, and grasses already waist high could hide a multitude of wildlife we could be only a few feet from and never see. “You have to be prepared,” Clark said, a nervous tic that we were later to discover represented the onset of malaria causing him appear as if he was constantly trying to shoo flies from his face, “for the possibility that we might not see anything at all.” But I’m not interested in just anything. I have come for one animal and one animal alone; perhaps the most allusive of them all—elephant.

We ride in silence, the sound of the motor and the tires as they chew at the road convincing us that if there is anything out here to see, it will be gone long before we get close to it. I barely look away from my binoculars to sneak a glance at the early morning sky when I feel the first rain drop. Instinctively I tuck my Canon under my photographer’s vest. The long, bulky 300mm lens rests uncomfortably on my ribs and I hope that the continuing patter of raindrops will soon pass.

The transition from drizzle to deluge is an undistinguishable one. One moment we are watching occasional drops blossom on the surface of our clothes and the next, just to remind us that this is Africa, the water comes down as if a giant cistern in the sky has just split directly over our heads. The Toyota lurches to a halt and we half fall, half dive to the ground, fumbling with slick door handles so that we might throw ourselves unceremoniously inside and sort out the mess of tangled limbs afterwards.

In the passenger seat, Chuck stares into the deafening gloom on the other side of his window and blows out his breath in a long, exasperated sigh. He doesn’t need to say anything. We all already know. If this keeps up, our trip and everything we spent on it is one colossal waste of time.

* * *

Burkina Faso rests in the middle of Western Africa, locked in by Benin, Togo and Ghana to the southeast, Mali to the west, Niger to the north, and Cote d’Ivoire to the south. At only twice the size of the state of Colorado, Burkina is one of West Africa’s smallest territories. The country is predominately flat, arid and scrubby. To the north, as one nears the Sahara desert, the vegetation transforms to sand dunes. Quite oppositely, the south becomes forested and in the east there are rolling plateaus and vast green woodlands fed by the country's three major rivers. Although serious efforts are underway to combat it, deforestation and desertification are a major threat to Burkina Faso. An unholy combination of drought, rapid population growth, overgrazing, and severe economic woes continue to plague the country. While Burkina may be one of West Africa’s smallest landmasses, it is also one of its most heavily populated. Due to its sporadic environment, population distribution is uneven and sketchy. While large northern tracts of land remain almost deserted, the south and central regions are bursting at the seams.

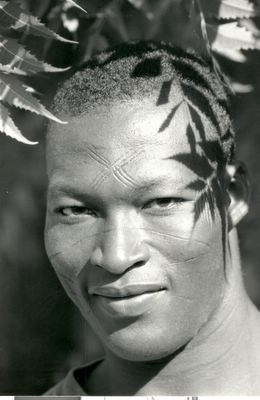

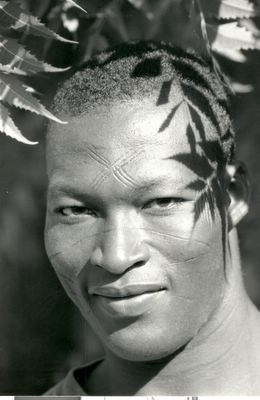

Though made up of over 60 tribes, the country of Burkina Faso is populated primarily by the descendants of the Mossi Empire. While the rest of Africa formed loose, non-hierarchical communities, the Mossi formed a blue-blooded kingdom to rival any the Western world created. Developing courts of law, administrative bodies, ministerial positions, and armies to protect the realm, the Mossi cemented their place in history as one of Africa’s most forward-thinking peoples. One of the few West African countries not predominantly Muslim, the Mossi’s might proved unassailable even to the hostile advances of their Muslim neighbors.

Stability was a trademark in Upper Volta (as it was then known) until the French began nosing around in 1897. Having already established colonies in the bordering countries, France decided to bring a little western imperialism to Upper Volta. The country was divided, subdivided, and then subdivided again. Generous chunks were parceled out to neighboring countries, while the population was scattered to work the French plantations in neighboring Cote d’Ivoire. While Cote d’Ivoire secured the position as the African golden child, Upper Volta was relegated to the position of the poor and ugly stepsister. It is not surprising that when colonization fell out of favor with the world, Upper Volta was one of the first to call for a return to independence. That road was to be a rocky one.

The country elected its first president in 1960. Maurice Yaméogo, himself a Mossi, unfortunately confused his election as a mandate to do whatever he wished. In an all-too-familiar African political saga, his regime of disastrous economic policies and rampant corruption led to riots in the streets. Yameogo was ousted from power in a 1965 military coup that, instead of setting up a stable power base, instead created a power vacuum under which Upper Volta was forced to endure nearly two decades of coups and counter coups. It was not until the charismatic Thomas Sankara took the reins that the country began to see hope. A young left-wing socialist, Sankara turned out to be something of a maverick. Showing himself to have a flair for public flourish, he renamed the country Burkina Faso (translated as “country of the upright people”). He immediately set in motion a package of radical social reforms that overhauled the country’s health care system, trained thousands of doctors and educators, built hundreds of schools, improved transportation, and curtailed ministerial privilege. While his unabashedly socialist policies made him a hero to the general populace, it demonized him among the elite. This, coupled with his chummy policies with Libya and a distain for western ideals signed his death warrant. In a coup worthy of Shakespeare, Sankara’s close friend and advisor, Blaise Compaore had him arrested, taken outside the city, and shot. Although immensely popular at first, the current Compaore government now finds itself mired in malaise and scandal.

Even so, Burkina is one of West Africa’s most stable countries, and its capital, Ouagadougou, one of the safest in which to live. More a large country town than big city, Ouaga, as it is affectionately called by locals, doesn’t boast many sights worthy of drawing tourist attention, but its wide, shady boulevards, relaxed atmosphere, and gregarious and hospitable people have made it immensely popular. If there is a birthplace of the renaissance of African art and culture, it is Ouagadougou. The FESPACO Film Festival, which takes place every other year, now rivals the Sundance Film Festival for cultural clout. During the alternate years, Burkina hosts the continent's largest craft market. Surprisingly, Burkina Faso is now the cultural darling of West Africa. After suffering the plebeian indignities of colonization and black birding, the Burkinabes have risen like phoenixes from the ashes, stronger both as a people and in their rich cultural identity. While easily one of the poorest countries on the planet, the people of Burkina Faso have fashioned for themselves the silk purse from the preverbal pigs’ ear.

Herman and Viola Engelgau, my grandparents, left their comfortable home in Portland, Oregon and came here in 1953, bearing with them their two small children, Carlyle, aged five and my mother, Charlene, aged three and a half. Long before either Hermie or Vi had met, both knew the call of God was upon their lives and both knew it was for only one place—the "Dark Continent."

They would remain in Africa for over 20 years, pouring the blood, sweat and tears of their young adult lives out in an offering for their God. Their children would call this strange land home and maintain a gravimetric bond to it that is, to this day, stronger than any geographical location on the planet.

This was Africa and for the first time in nearly 30 years my family was returning home.

And I was there to see it.

There wasn’t much to see on the hours leading up to our decent into Burkina Faso. Small monitors above our seats, slaved to geo-synchronous positioning satellites, consistently updated the vital statistics of our voyage. For much of that time, a small digital representation of our plane crept along an expanse on the map that simply read: Sahara. The expanse wasn’t just on the map, it was below us, in front of us, behind us, and all around us stretching for as far as the eye could see. As disconcerting as open ocean flight, this was a sea of unbroken, uninterrupted, unremitting brown.

By the time the cockpit did finally announce our final decent, the brown had given way somewhat to splotchy patches of vegetative green, and black serpentine rivers. As the earth rose to meet us and the land gained definition, small huts began to take shape and the occasional vehicle could be seen, a plume of dust feathering in its wake. There was a palpable sense of exhilaration in the cabin as the Sabena 737 touched down with a hard jolt on Ouagadougou International Airport’s single runway and careened around to make its way toward the tiny, unassuming terminal.

Hot. Humid. Brown. But oh so much sky. I was busy cataloging my first African impressions in my mind as we descended the stairs to the tarmac that I nearly didn’t hear my grandfather’s voice. Half joking, half serious he said to me, “Brandon, you’re standing on holy ground.”

If Ouagadougou looked like an oversized mud village from the air, it improved very little from the ground. Departing the airport and the crush of bodies it represented, we traced our way through the parking lot to a waiting car just as a hard rain began to fall. Pastor Pawentaore, President of the Assemblies of God of Burkina drives us. He is 50ish, good-looking, and immaculately dressed. Like hyperactive children having just come off a thrilling amusement park ride and excitedly sharing the experience with others, the din of our voices inside the car easily matches that of the rain splattering against the windows outside. While I half listen to the conversation, the one sense that is getting my undivided attention is sight. As Pastor Pawentaore weaves his car through the metallic tangle of exhaust spewing mopeds (Ouagadougou, as we are to discover later, is dubbed the “Hong Kong of Africa” due to its glut of moped traffic—a title richly deserved) my eyes see things few Americans can comprehend. Tiny ramshackle wooden shacks, composed of whatever raw materials were lying around and held together with rope and rusty nails line each dirt road bisecting the city. Some advertise food, others car parts, others hair salons. Donkeys pull gigantically overburdened carts saturated with wares, wood, or rock. Buses, looking as it they were pulled from a demolition lot earlier that day, rumble opposite us, roofs packed nearly double their height with a hodgepodge of baggage. Rubbish heaps up at every corner and is strewn on every patch of bare ground as if painted there. Chickens, goats and emaciated dogs dart in and out of the legs of naked children, in search of food. Squalor is the only word that I can think of to describe what I’m observing. “You’re seeing poverty at its worst.” My mother will tell me the following day on a driving tour of the city. “The world doesn’t get any poorer than this.”

My thoughts are interrupted by Pastor Pawentaore who addresses the car saying, “There are several different kinds of missionaries: There are those who are called but do not come. There are those who are called but come begrudgingly, hating everything to do with the mission field. There are those who are called, come willingly, but never make friends here and hence have no lasting impact. There are those who come, do good works, but leave and are never heard from again.” He is interrupted by my grandmother, “There are those who come and you wish would leave and never be heard from again!” The laughter in the car lasts for several moments, but in the end is tempered by a powerful honesty as Pastor Pawentaore looks at my grandparents and says, “Then there are those who come, make a powerful impact on those they minister to, and even though they must eventually leave, never lose contact and eventually return.”

A few minutes later we arrive at the Assemblies of God mission compound and pull up to a tree-encased house that I find out a few minutes later, my grandfather had built. Soaked and weary from travel, we lug our suitcases inside and share some much needed bottles of chilled Coke-a-Cola. As the rain continues to fall, hard and noisily on the metallic roof, I fall into a deep lounge chair and begin sorting out my thoughts on paper. What I saw this evening was only the minutest glimpse of Africa. With a full two weeks ahead of me, what wonders, what thrills, what heart-wrenching agonies was I yet to see?

That night I went to bed, seduced by a lullaby utterly foreign to my ears. As I surrendered to slumber, it was to the music of Muslim criers and the incessant high-pitched chatter of hundreds of fruit bats suffusing the trees outside my window.

Nazinga Game Ranch

Burkina Faso, West Africa

The sun has been up for some time but if I hadn’t been up since before 5 o’clock to see it rise, I’d never have known it. I’m sitting precariously on the roof of a Toyota Land Cruiser, fingers braided awkwardly through the latticework of the vehicle's luggage rack, watching the vast African horizon buck and swell with every uneven inch the truck consumes. The deep green of the bush appears in muted tones beneath a sky as black as pitch. Sinister clouds--heaving things that move as if alive and seem low enough to glide your fingers across--dominate the heavens. We’ve barely left our camp and already it looks as if the heavens are going to be rent asunder.

Atop the car beside me sit my mother and a young Dutch couple. My mother’s hair blows in the ozone-laden wind and her eyes gleam with child-like pleasure. I know she loves this sort of thing. While Karin seems content to curl her legs beneath her, Indian-style, her husband, Robert, with legs longer than spears, appears utterly uncomfortable. Ultimately he throws his legs over the side, opting to sit sidesaddle.

It has been only fifteen minutes since we left our warm cups of Nescafe instant coffee behind in the ranch mess-hall and already the punishing road—rocky, pitted with gaping holes, and sodden with deep pools of brown water—is giving us menacing previews of what our backsides are going to feel like come day’s end. If it weren’t for the sheer pleasure of the experience, we might all think it perfectly absurd that we’re clinging for dear life atop the roof of a moving SUV while its cavernous interior cradles only two occupants. At the wheel is our African driver, who comes included with the truck’s rental package. Sitting shotgun is Clark Lungren. A Canadian whose parents were missionaries, Clark grew up in Africa and has never left. The Nazinga game ranch we now explore is his creation—the largest, most densely populated one of its kind in West Africa. For the last 20 some years, Clark and those he’s trained have sought to strike a delicate balance between the needs of the human population and the necessity to protect the land and its animal inhabitants from human predators. Through a wise mixture of limited game cropping, local employment, eco-tourism and anti-poaching measures, Nazinga has become such a success that the government of Burkina Faso recently wrested control away from its founders so that it might benefit from the reserve’s bounty and prestige. These are all issues, we have learned, that Clark is more than ready to discuss ad-nauseam.

Listing hard to the left, my body tenses as I prepare to leap off should the Land Cruiser overturn. “You ever roll one of these?” I yell to Chuck as we right ourselves, surging from a frothing sea of mud. “Never,” he shouts back. His reply gives me some solace. Still, there’s a first time for everything.

There isn’t much talk. Most of the time its strained whispers, half-snatched away by the wind, which make up our conversation. We’re all too busy to talk, nor do we want to make the noise. We keep our faces shoved firmly in binoculars, our eyes darting across the landscape for any signs of life. The ranch abounds with animal activity although our arrival in the rainy season severely limits what we might view. Trees heavy with thick leaves, foliage in deep bloom, and grasses already waist high could hide a multitude of wildlife we could be only a few feet from and never see. “You have to be prepared,” Clark said, a nervous tic that we were later to discover represented the onset of malaria causing him appear as if he was constantly trying to shoo flies from his face, “for the possibility that we might not see anything at all.” But I’m not interested in just anything. I have come for one animal and one animal alone; perhaps the most allusive of them all—elephant.

We ride in silence, the sound of the motor and the tires as they chew at the road convincing us that if there is anything out here to see, it will be gone long before we get close to it. I barely look away from my binoculars to sneak a glance at the early morning sky when I feel the first rain drop. Instinctively I tuck my Canon under my photographer’s vest. The long, bulky 300mm lens rests uncomfortably on my ribs and I hope that the continuing patter of raindrops will soon pass.

The transition from drizzle to deluge is an undistinguishable one. One moment we are watching occasional drops blossom on the surface of our clothes and the next, just to remind us that this is Africa, the water comes down as if a giant cistern in the sky has just split directly over our heads. The Toyota lurches to a halt and we half fall, half dive to the ground, fumbling with slick door handles so that we might throw ourselves unceremoniously inside and sort out the mess of tangled limbs afterwards.

In the passenger seat, Chuck stares into the deafening gloom on the other side of his window and blows out his breath in a long, exasperated sigh. He doesn’t need to say anything. We all already know. If this keeps up, our trip and everything we spent on it is one colossal waste of time.

* * *

Burkina Faso rests in the middle of Western Africa, locked in by Benin, Togo and Ghana to the southeast, Mali to the west, Niger to the north, and Cote d’Ivoire to the south. At only twice the size of the state of Colorado, Burkina is one of West Africa’s smallest territories. The country is predominately flat, arid and scrubby. To the north, as one nears the Sahara desert, the vegetation transforms to sand dunes. Quite oppositely, the south becomes forested and in the east there are rolling plateaus and vast green woodlands fed by the country's three major rivers. Although serious efforts are underway to combat it, deforestation and desertification are a major threat to Burkina Faso. An unholy combination of drought, rapid population growth, overgrazing, and severe economic woes continue to plague the country. While Burkina may be one of West Africa’s smallest landmasses, it is also one of its most heavily populated. Due to its sporadic environment, population distribution is uneven and sketchy. While large northern tracts of land remain almost deserted, the south and central regions are bursting at the seams.

Though made up of over 60 tribes, the country of Burkina Faso is populated primarily by the descendants of the Mossi Empire. While the rest of Africa formed loose, non-hierarchical communities, the Mossi formed a blue-blooded kingdom to rival any the Western world created. Developing courts of law, administrative bodies, ministerial positions, and armies to protect the realm, the Mossi cemented their place in history as one of Africa’s most forward-thinking peoples. One of the few West African countries not predominantly Muslim, the Mossi’s might proved unassailable even to the hostile advances of their Muslim neighbors.

Stability was a trademark in Upper Volta (as it was then known) until the French began nosing around in 1897. Having already established colonies in the bordering countries, France decided to bring a little western imperialism to Upper Volta. The country was divided, subdivided, and then subdivided again. Generous chunks were parceled out to neighboring countries, while the population was scattered to work the French plantations in neighboring Cote d’Ivoire. While Cote d’Ivoire secured the position as the African golden child, Upper Volta was relegated to the position of the poor and ugly stepsister. It is not surprising that when colonization fell out of favor with the world, Upper Volta was one of the first to call for a return to independence. That road was to be a rocky one.

The country elected its first president in 1960. Maurice Yaméogo, himself a Mossi, unfortunately confused his election as a mandate to do whatever he wished. In an all-too-familiar African political saga, his regime of disastrous economic policies and rampant corruption led to riots in the streets. Yameogo was ousted from power in a 1965 military coup that, instead of setting up a stable power base, instead created a power vacuum under which Upper Volta was forced to endure nearly two decades of coups and counter coups. It was not until the charismatic Thomas Sankara took the reins that the country began to see hope. A young left-wing socialist, Sankara turned out to be something of a maverick. Showing himself to have a flair for public flourish, he renamed the country Burkina Faso (translated as “country of the upright people”). He immediately set in motion a package of radical social reforms that overhauled the country’s health care system, trained thousands of doctors and educators, built hundreds of schools, improved transportation, and curtailed ministerial privilege. While his unabashedly socialist policies made him a hero to the general populace, it demonized him among the elite. This, coupled with his chummy policies with Libya and a distain for western ideals signed his death warrant. In a coup worthy of Shakespeare, Sankara’s close friend and advisor, Blaise Compaore had him arrested, taken outside the city, and shot. Although immensely popular at first, the current Compaore government now finds itself mired in malaise and scandal.

Even so, Burkina is one of West Africa’s most stable countries, and its capital, Ouagadougou, one of the safest in which to live. More a large country town than big city, Ouaga, as it is affectionately called by locals, doesn’t boast many sights worthy of drawing tourist attention, but its wide, shady boulevards, relaxed atmosphere, and gregarious and hospitable people have made it immensely popular. If there is a birthplace of the renaissance of African art and culture, it is Ouagadougou. The FESPACO Film Festival, which takes place every other year, now rivals the Sundance Film Festival for cultural clout. During the alternate years, Burkina hosts the continent's largest craft market. Surprisingly, Burkina Faso is now the cultural darling of West Africa. After suffering the plebeian indignities of colonization and black birding, the Burkinabes have risen like phoenixes from the ashes, stronger both as a people and in their rich cultural identity. While easily one of the poorest countries on the planet, the people of Burkina Faso have fashioned for themselves the silk purse from the preverbal pigs’ ear.

Herman and Viola Engelgau, my grandparents, left their comfortable home in Portland, Oregon and came here in 1953, bearing with them their two small children, Carlyle, aged five and my mother, Charlene, aged three and a half. Long before either Hermie or Vi had met, both knew the call of God was upon their lives and both knew it was for only one place—the "Dark Continent."

They would remain in Africa for over 20 years, pouring the blood, sweat and tears of their young adult lives out in an offering for their God. Their children would call this strange land home and maintain a gravimetric bond to it that is, to this day, stronger than any geographical location on the planet.

This was Africa and for the first time in nearly 30 years my family was returning home.

And I was there to see it.

There wasn’t much to see on the hours leading up to our decent into Burkina Faso. Small monitors above our seats, slaved to geo-synchronous positioning satellites, consistently updated the vital statistics of our voyage. For much of that time, a small digital representation of our plane crept along an expanse on the map that simply read: Sahara. The expanse wasn’t just on the map, it was below us, in front of us, behind us, and all around us stretching for as far as the eye could see. As disconcerting as open ocean flight, this was a sea of unbroken, uninterrupted, unremitting brown.

By the time the cockpit did finally announce our final decent, the brown had given way somewhat to splotchy patches of vegetative green, and black serpentine rivers. As the earth rose to meet us and the land gained definition, small huts began to take shape and the occasional vehicle could be seen, a plume of dust feathering in its wake. There was a palpable sense of exhilaration in the cabin as the Sabena 737 touched down with a hard jolt on Ouagadougou International Airport’s single runway and careened around to make its way toward the tiny, unassuming terminal.

Hot. Humid. Brown. But oh so much sky. I was busy cataloging my first African impressions in my mind as we descended the stairs to the tarmac that I nearly didn’t hear my grandfather’s voice. Half joking, half serious he said to me, “Brandon, you’re standing on holy ground.”

If Ouagadougou looked like an oversized mud village from the air, it improved very little from the ground. Departing the airport and the crush of bodies it represented, we traced our way through the parking lot to a waiting car just as a hard rain began to fall. Pastor Pawentaore, President of the Assemblies of God of Burkina drives us. He is 50ish, good-looking, and immaculately dressed. Like hyperactive children having just come off a thrilling amusement park ride and excitedly sharing the experience with others, the din of our voices inside the car easily matches that of the rain splattering against the windows outside. While I half listen to the conversation, the one sense that is getting my undivided attention is sight. As Pastor Pawentaore weaves his car through the metallic tangle of exhaust spewing mopeds (Ouagadougou, as we are to discover later, is dubbed the “Hong Kong of Africa” due to its glut of moped traffic—a title richly deserved) my eyes see things few Americans can comprehend. Tiny ramshackle wooden shacks, composed of whatever raw materials were lying around and held together with rope and rusty nails line each dirt road bisecting the city. Some advertise food, others car parts, others hair salons. Donkeys pull gigantically overburdened carts saturated with wares, wood, or rock. Buses, looking as it they were pulled from a demolition lot earlier that day, rumble opposite us, roofs packed nearly double their height with a hodgepodge of baggage. Rubbish heaps up at every corner and is strewn on every patch of bare ground as if painted there. Chickens, goats and emaciated dogs dart in and out of the legs of naked children, in search of food. Squalor is the only word that I can think of to describe what I’m observing. “You’re seeing poverty at its worst.” My mother will tell me the following day on a driving tour of the city. “The world doesn’t get any poorer than this.”

My thoughts are interrupted by Pastor Pawentaore who addresses the car saying, “There are several different kinds of missionaries: There are those who are called but do not come. There are those who are called but come begrudgingly, hating everything to do with the mission field. There are those who are called, come willingly, but never make friends here and hence have no lasting impact. There are those who come, do good works, but leave and are never heard from again.” He is interrupted by my grandmother, “There are those who come and you wish would leave and never be heard from again!” The laughter in the car lasts for several moments, but in the end is tempered by a powerful honesty as Pastor Pawentaore looks at my grandparents and says, “Then there are those who come, make a powerful impact on those they minister to, and even though they must eventually leave, never lose contact and eventually return.”

A few minutes later we arrive at the Assemblies of God mission compound and pull up to a tree-encased house that I find out a few minutes later, my grandfather had built. Soaked and weary from travel, we lug our suitcases inside and share some much needed bottles of chilled Coke-a-Cola. As the rain continues to fall, hard and noisily on the metallic roof, I fall into a deep lounge chair and begin sorting out my thoughts on paper. What I saw this evening was only the minutest glimpse of Africa. With a full two weeks ahead of me, what wonders, what thrills, what heart-wrenching agonies was I yet to see?

That night I went to bed, seduced by a lullaby utterly foreign to my ears. As I surrendered to slumber, it was to the music of Muslim criers and the incessant high-pitched chatter of hundreds of fruit bats suffusing the trees outside my window.

6 Comments:

Yeah! Africa. Vuestra historia favorita de mio.

Or mi historia favorita de vuestro. Whatever.

Is that African?

No, but tengo un examen today, I'm trying to get in the groove-o.

Ay caribe!

So good "revisiting" that wonderful time, made even more special by being able to see it through your eyes!

Wow, wonderful writing! You've captured the Burkina Faso I remember! My family and I lived there from 1983-1992 but I guess we were the kind of missionaries who leave and are never heard from again! Excellent writing, keep up the good work.

Steve, dit Ouedraogo Etienne

Post a Comment

<< Home