"What Kind of People are These?"

This is a spectacularly extraordinary article by a Benedictine sister by the name of Joan Chittister, a best-selling author and well-known international lecturer on topics of justice, peace, human rights, women's issues, and contemporary spirituality in the Church and in society.

I've transcribed the entire article here, or you can read it at the National Catholic Reporter where she pens the column "From Where I Stand."

"What Kind of People are These?"

by Joan Chittister

Originally published in the National Catholic Reporter

The country that went through the rabid slaughter of children at Columbine high school several years ago once again stood stunned at the rampage in a tiny Amish school this month.

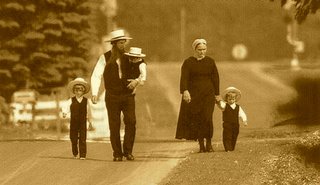

We were, in fact, more than unusually saddened by this particular display of viciousness. It was, of course, an attack on 10 little girls. Amish. Five dead. Five wounded. Most people called it "tragic." After all, the Amish represent no threat to society, provide no excuse for the rationalization of the violence so easily practiced by the world around them.

Nevertheless, in a nation steeped in violence -- from its video games to its military history, in foreign policy and on its streets -- the question remains: Why did this particular disaster affect us like it did? You'd think we'd be accustomed to mayhem by now.

But there was something different about this one. What was it?

Make no mistake about it: the Amish are not strangers to violence.

The kind of ferocity experienced by the Amish as they buried the five girl-children murdered by a crazed gunmen two weeks ago has not really been foreign to Amish life and the history of this peaceful people.

This is a people born out of opposition to violence -- and, at the same time, persecuted by both Catholics and Protestants in the era before religious tolerance. Having failed to adhere to the orthodoxy of one or the other of the controlling theocracies of their home territories, they were banished, executed, imprisoned, drowned or burned at the stake by both groups.

But for over 300 years, they have persisted in their intention to be who and what they said they were.

Founded by a once-Catholic priest in the late 17century, as part of the reformist movements of the time, the Mennonites -- from which the Amish later sprung -- were, from the beginning, a simple movement. They believe in adult baptism, pacifism, religious tolerance, separation of church and state, opposition to capital punishment, and opposition to oaths and civil office.

They organize themselves into local house churches. They separate from the "evil" of the world around them. They live simple lives opposed to the technological devices -- and even the changing clothing styles -- which, in their view, encourage the individualism, the pride, that erodes community, family, a righteous society. They work hard. They're self-sufficient; they refuse both Medicare and Social Security monies from the state. And though the community has suffered its own internal violence from time to time, they have inflicted none on anyone around them.

Without doubt, to see such a peaceful people brutally attacked would surely leave any decent human being appalled.

But it was not the violence suffered by the Amish community last week that surprised people. Our newspapers are full of brutal and barbarian violence day after day after day -- both national and personal.

No, what really stunned the country about the attack on the small Amish schoolhouse in Pennsylvania was that the Amish community itself simply refused to hate what had hurt them.

"Do not think evil of this man," the Amish grandfather told his children at the mouth of one little girl's grave.

"Do not leave this area. Stay in your home here." the Amish delegation told the family of the murderer. "We forgive this man."

No, it was not the murders, not the violence, that shocked us; it was the forgiveness that followed it for which we were not prepared. It was the lack of recrimination, the dearth of vindictiveness that left us amazed. Baffled. Confounded.

It was the Christianity we all profess but which they practiced that left us stunned. Never had we seen such a thing.

Here they were, those whom our Christian ancestors called "heretics," who were modeling Christianity for all the world to see. The whole lot of them. The entire community of them. Thousands of them at one time.

The real problem with the whole situation is that down deep we know that we had the chance to do the same. After the fall of the Twin Towers we had the sympathy, the concern, the support of the entire world.

You can't help but wonder, when you see something like this, what the world would be like today if, instead of using the fall of the Twin Towers as an excuse to invade a nation, we had simply gone to every Muslim country on earth and said, "Don't be afraid. We won't hurt you. We know that this is coming from only a fringe of society, and we ask your help in saving others from this same kind of violence."

"Too idealistic," you say. Maybe. But since we didn't try, we'll never know, will we?

Instead, we have sparked fear of violence in the rest of the world ourselves. So much so, that they are now making nuclear bombs to save themselves. From whom? From us, of course.

The record is clear. Instead of exercising more vigilance at our borders, listening to our allies and becoming more of what we say we are, we are becoming who they said we are.

For the 3,000 dead in the fall of the Twin Towers at the hands of 19 religious fanatics, we have more than 2,700 U.S. soldiers now killed in military action, more than 20,600 wounded, more than 10,000 permanently disabled. We have thousands of widows and orphans, a constitution at risk, a president that asked for and a Congress that just voted to allow torture, and a national infrastructure in jeopardy for want of future funding.

And nobody's even sure how many thousand innocent Iraqis are dead now, too.

Indeed, we have done exactly what the terrorists wanted us to do. We have proven that we are the oppressors, the exploiters, the demons they now fear we are. And -- read the international press -- few people are saying otherwise around the world.

From where I stand, it seems to me that we ourselves are no longer so sure just exactly what kind of people we have now apparently become.

Interestingly enough, we do know what kind of people the Amish are -- and, like the early Romans, we, too, are astounded at it.

"Christian" they call it.

17 Comments:

Thanks for sharing that.

Agreed, great article, thanks for posting it. I had wondered what would have happened if our leadership had initiated such a Christian response. How would the rest of the nation had responded? Would the other side of the aisle have taken up the war chant? How would the Islamic world have responded? Would they have been shamed and join in ridding their religion of its trash or would the trash have risen up and attacked US all the more with the impunity they did?

Paul

I'll be addressing your very comments, Paul, in one of my next posts.

Wow. Fantastic. Fantastic.

Thanks for sending that....

Yes. I agree. And the Amish are doing what believing people ought to do!

Although it's worth saying that the parallels aren't precise. The crazed gunman is easier to forgive than a massive group of people who continue to breathe threats [if that's what they are doing]. If the crazed gunman came from a long line of gunman who killed Amish people, and he had a stack more where he came from, it is more complex to know what to do.

Not justifying anything. Just point out that the parallels aren't quite the same.

Forgiveness isn't parallel.

That's what makes it forgiveness. And a command.

One or a thousand enemies. One or a thousand slights.

Forgive. End of the matter.

I think you may be right.

But it is complex. Like telling an abuse victim -- one whose abuser is still a threat -- to forgive.

Just complex...

Sure, sure.

What does Yancey say? The math of grace is bad.

That's good news...

Exactly.

Thank you Brandon. It is good to read this.

So often we make this an either-or equation: either we forgive or we open a can of whoop-ass. The real question is whether we are pursuing justice or vengeance. I don't think the Amish would advocate a completely lawless society where no one is held accountable for their actions. It they did, I think they would be wrong.

There is a significant difference between using force to stop the man who is beating your child and pulling the man off your child and stomping his face to pulp as an act of revenge.

For the professing follower of Christ, forgiveness is not an option to be considered like your stance on capital gains taxes or embryonic stem cell research, it's a command. Non-negotiable.

I agree that the killing of the 5 girls is qualitatively different than 9/11, but not by much.

Have I said that Reacher is awesome?

Brandon, thanks for posting the article. I, too, have marveled at the beauty of the forgiveness extended by the Amish families. And yet, as your readers have pointed out, it is exactly what we are called to do. It is so difficult when we see it from our natural human response. Human nature lends itself toward giving as good as you get, exacting vengeance, getting even. Jesus' command to forgive our enemies and those who have harmed us goes against the grain of human nature AND the culture around us, which is why the world has found the Amish response so astounding.

Reacher is right about our extremes of responding either with forgiveness or revenge (I belive he termed it whoop-ass); often I think which extreme we choose is also dependent upon who the offending party is - we tend to be more forgiving, for example, of those we love and value, while those we deem unworthy of our forgiveness receive our vengefulness. Forgiveness is definitely not an option, we are indeed to forgive, as you said (whether an individual or an entire people-group) - end of the matter.

As someone who has been both the recipient of abuse and a number of betrayals, I found that forgiveness came at the end of a very long journey, which I first had to complete before I could forgive those who hurt me. Forgiveness, when practiced, can begin to become part of the pattern of the redeemed life and gets a little easier, I've discovered, as I continue the pattern. It has never been easy. And then there are the many scenarios pointed out by your readers that, again by our human understanding, seem to somehow qualify the terms of forgiveness. Only by God's grace...

You are all such beautiful people. Reacher and Anonymous, especially: you have so well stated what needs to be said to many who profess to follow Christ.

For those of us who don't, the argument is no less necessary. As I posted a few months ago, WE MUST MOVE BEYOND REVENGE.

We are allegedly a "higher" species, more evolved, with the ability to reason. We have moved beyond rape, beyond constant warring for territory, in our quest to become a Civilized race.

Even (or perhaps especially) for those who can't quite bring themselves to forgive, the movement BEYOND revenge is necessary.

It's what the Death Penalty in the US is all about: Revenge. It's not Justice. We need to learn to separate the two.

It saddens me how primitive our "dinosaur brains" remain at times. It moves me to tears to hear that the people of the Amish community had the humanity to do what we should all be able to do, to continue to call ourselves Human.

I wish I could figure out how to tell people they must move beyond revenge, because they so often seem completely incapable of it. How can we start this?

Greetings~ How neat to see so many thoughtful comments on such a deep issue. "anonymous," I thank you for sharing from the deep places of your heart (not easy to do).

I have a sister and a cousin who joined the Mennonite "segment" of the Church after entering adulthood, and from them, I have heard perspectives on non-violent resistance to evil that have been truly life-changing.

Pacifism is about incredible strength. It is active, not passive: perpetrators of evil are confronted with their evil, but instead of doing so by repaying their evil with more evil, they are confronted with good. "Conflict transformation," as it is often called, is not merely letting go of revenge--it is the offering of grace, forgiveness, compassion, and mercy. It is the modeling of the way things ought to be--how we should be living toward each other in the human family--even in the face of horrific wrongdoing, and at the expense of one's own well-being and, perhaps, one's life.

It is primal to respond to threats to our life with violence. Responding from a place grounded in human dignity, however, can transform life-threatening situations.

I had the privilege of hearding Paul Rusesabagina (the man behind "Hotel Rwanda") speak last year on this topic, and thought how similar his approach was to that described by my sister in her conflict transformation "classes." Even as armed militiamen poured over the wall of his compound (at home), he remained calm and spoke to them as if they were "normal" human beings, instead of crazed murderers--and speaking to that capacity within them jolted them out of their murderous state of mind. (Granted, this will not always happen, but we do not do the right thing to achieve a certain outcome--we do the right thing because it is the only way to be.)

Anyway, I have found it very enriching to hear from this part of the Church body, and I thank you for posting this, Brandon.

Blessings~

Robin-- I think your question about moving beyond revenge is such a good one. I think so much about forgiveness and how to reach people about this issue (that is, most especially those who have experienced egregious victimization).

There are so many ways of framing the ontological grounding of forgiveness: appeals to shared humanity, especially shared capacity for wrongdoing; the appeals to understand ourselves as creatures rather than Creator and what that means for "sitting in the judgment seat"; appeals for understanding the perpetrator and exonerating them based on their brokenness; appeals to the pragmatics, as it were, of cycles of revenge and focusing on how loving our posterity entails letting go of revenge for their sake... (Some of these narratives, I find more compelling and supportable than others, of course.)

Certainly, religion has given us a useful framework for such things for millenia. I keep finding, though, that people still struggle a great deal with understanding forgiveness (e.g., thinking it means not being angry any more, having to forget the wrong that transpired, having to maintain a relationship with the offender...sigh).

So, yeah, I think working on our metaphysical (ontological) grounding for forgiveness (on what basis/why do I extend forgiveness?) is an important mental exercise, given the profound social and emotional consequences of our beliefs around this issue...

Daria : )

Post a Comment

<< Home