Splendor and Squalor: PART II

Our stay in Africa was to be divided in two nearly equal halves. These parts, mirroring my family’s history in Burkina, would place us for the first week in the village of Boromo, after which time we would return to Ouaga for the latter half of our trip. When my grandparents set out for the mission field, they first went to Paris for a year to learn French. The next stop was to Ouagadougou where they started over again and for the next year, learned the local dialect of More (pronounced “Moore-eh”). But Ouagadougou was not to be their home. Their home for almost the next decade would be several hours to the southwest in the medium-sized village of Boromo.

Traveling to Boromo was nothing like it was when my grandparents lived here. They relate stories of a half-day of travel on a wide dirt road, chocking on the red dirt that coated every surface of thier car, clothes and bodies. Our trip today takes barely over two hours and is sped along by a newly installed paved road that finds my grandparents shaking their heads in astonishment. The ground here is a bright red contrasted sharply with the thick green of the vegetation that flashes past our car in dense emerald smudges. This is the rainy season and the face Burkina is showing the world is an utterly deceptive one to those who do not understand the African climate. Mere months from now this green will be a distant memory, as will the leaves and foliage that clothe every tree. With unbearably stifling temperatures, the water of the rainy season will evaporate into the burnt browns of the dry season and the African bush will put on the face of a thing more dead than alive. I, for one, am glad I came when I did.

Memories, poignant and as starkly defined as burnished marble flit about my family like so many invisible butterflies as we pull up to the house my grandfather built and in which they raised their children. I find myself snapping pictures of them like some sort of insensitive photojournalist, capturing the moments when they cross the thresholds of the various rooms and the tears soak through and overwhelm them. There will be many tears in the next few days as we amble along the old paths and ingest sights not seen or perhaps even thought of in three decades.

* * *

A parade of people. This is the only possible way to describe the wave upon wave of visitors that came to greet my grandparents and mother. Every day, from shortly after sunrise, to well after dark, a steady stream of visitors fed its way into the house like a human tributary. There are very few private moments on this trip and even fewer to catch one's breath. The people come from near and far, staying for only a few moments or for several days. But they all come with one intent—to fall on the neck of “Papa” and “Madam” and “little Charlene,” to kiss and hold them and let their tears mingle as their lives once did. Pastors and bible-school graduates, old cooks, drivers and groundskeepers, masons and iron-workers, church layman and government officials, Christian and Muslim--they all come.

I watch this with the odd perspective of a well-informed fly on the wall. My grandparents seem charged with electricity and more in their element than I have ever seen them before. It is strangely disconcerting and equally compelling to watch your family chatter way in a language far more foreign than any taught on western campuses and one in which I have only heard when there was a need to secretly converse about that year’s Christmas presents. “Don’t you know,” I am told later, “they speak More in heaven!”

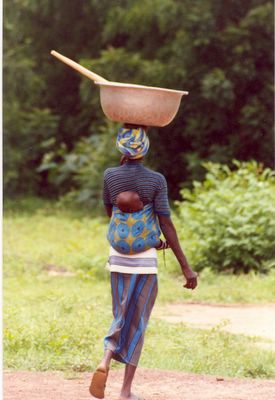

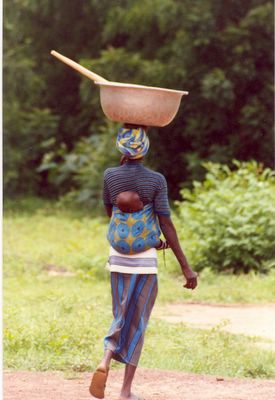

The visitors to the house (still in use by French missionaries now in Paris for medical furlough) are a marvelously beautiful bunch. There is no smile in the world at all more beautiful than that made when pearly white teeth break open on deep, black African skin. Tribal scars line and swirl their faces. Melodic voices resonate through teeth chiseled to fine points. The women move with a deliberate and graceful poise. It is of little surprise they can walk (and even ride) with such large bundles atop their heads. The children bear a subservience to their elders that is equal parts refreshing and maddening. They embrace us, covering us with a multitude of kisses and grasp our hands repeatedly while simultaneously chirping contentedly. Their face, beaming, cannot hide the joy of the Lord.

“My heart is full.” One visitor exclaims.

“Not as full as ours,” my grandmother replies.

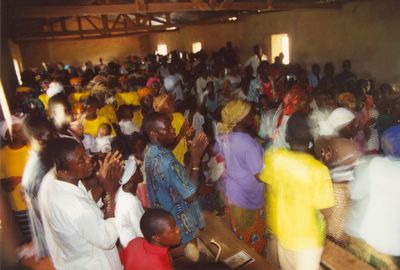

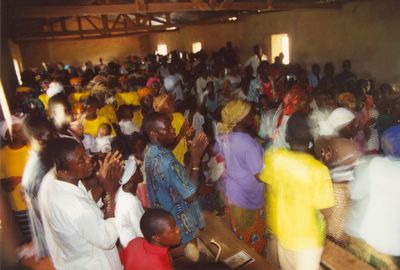

That Sunday, sitting in the church my grandfather constructed and ministered in, we are treated to a service that lasts over five hours. With the sounds of African drums and voices still ringing in our ears, I discover first-hand just how loved my grandparents really are. Packed to capacity, the crowds line the outside of the church, faces peering intently through the slated windows for any glimpse inside.

Eloquent tributes (“They loved us with their hearts, not just their teeth”) and lavish gifts are presented and when my grandmother stands to address the gathering, it is with a broken voice that she announces, “Today, I have tasted heaven.”

Later in the trip, after a similar evening, my grandfather sits silently in the restroom for a long time. When my grandmother asks him through the door if he’s ok, he replies, “I’m just in here bursting my buttons. I’ve never felt so much honor and reverence in my life.”

“Your grandfather always stands up so much straighter here.” My grandmother confides to me afterwards.

* * *

I love the sound of my grandfather’s voice. He has a James Earl Jones quality which, what it lacks is depth of tone, it matches in power and inflection. Be I boy or man, there are few better moments I have experienced than sitting at my grandparent's Portland breakfast table, full on homemade toast and jelly, listening to my grandfather read devotions.

Nearly 80, hunched with time and plagued by pain in his hands, hips and knees, my grandfather is no longer the man I see in the old slides of Africa he loves to pull from the attic every Christmas visit. He cannot move as fast or stand as straight, but I realize a hundred times over, as I stand beside him, taller by nearly two feet, that my grandfather is a giant of a man.

Listening to my grandfather preach several times this trip, I am painfully reminded that it may be one of my last times to be so honored. I smile to myself as he confuses the languages of his sermon, vacillating between English, More and French without noticing he’s made the switch. If a grandson can be more proud of his grandparents than I am, I cannot see how. They are too humble to swell with the pride I allowed myself to be infused with on this trip. Watching my grandparents together (she is ramrod straight, walks more briskly than any 18-year-old, and seems in every way a polar opposite of her husband) I was daily overcome with the realization that my grandparents are truly great human beings who have done truly great things in this world. I could never have comprehended to what degree that was true had I not “tagged along” on this trip.

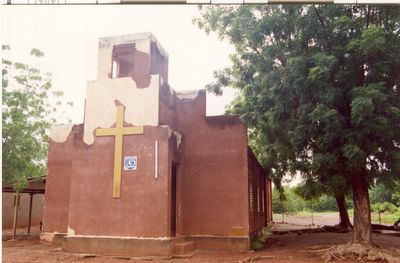

Using Boromo as our base camp of sorts, we journeyed daily to numerous villages that lay in the outlying provinces. Villages with names like Oury, Pompoi, and Bagesi. In each, hundreds of people swarmed from their huts and houses to greet us as we pulled up to the local church building. My grandfather had built nearly every one. The small blue plaque above each entryway denoting the church as of the “Assemblees de Dieu” had become so very familiar that it prompted one person to comment that the three things you see most in Burkina these days are “Blue jeans, Coke-a-Cola, and Assemblies of God churches.”

Nearly every church is packed to overflowing. At many villages, larger buildings are being constructed a stone's throw away. At Ouhabo, we visit with the local congregation as they toil under the hot sun. Half naked women slap mixtures of mud and tar over sun-dried mud bricks and smear it flat. Behind them, several men stomp in a pit of muck, preparing the next batch. The roof is the only thing they cannot provide. The rains make anything other than a metal roof impossible and such materials are nearly unattainable or unfeaisibly expensive. They build the church anyway, confidant that God will provide.

Lunch comes in the form of delicious peanut and chicken sauces poured overtop heaping helpings of white rice. Those who believe that the only reason for solid food in the first place is so that there is something on which to put sauce will love the food in Burkina--everything comes with sauce. A stir of the saucepot reminds one of the more adventuresome nature of the trip as chicken feet and heads bob to the surface. Each visit brought more gifts--from clothing, carved sculptures, leather goods, guinea-hen eggs and armloads of struggling chickens that would find their way noisily to the cab of the pickup each day and tastily to our dinner plates each night. Utterly without material possessions, these people gave all that they had; more than they could afford to give, but they gave it willingly, rejoicingly. Without knowing where their next meal was coming from, they happily presented us with more than we could ever hope to eat.

“Africa is not about sights, it is about people,” said Benjamin Yanogo, a local pastor who was to be our trip’s chaffer, translator, horticulturist and in the end, our dearest of friends. Merely one in an utterly magnificent family, he will knit himself to our hearts in the short weeks we are there like no other. “Here, there are no real monuments to see, only life itself.”

At one of the churches we visit, a man opens his Bible and withdraws a bookmark, yellowed with age. On it, my grandparents smile at me, practically as young as I am now. Not Grampa and Grama, but Hermie and Vi, youthful and virile. The bookmark has been there, tucked away safely in the folds of those pages for half a century.

And it hits me—what a life-validating trip! What an utterly authenticating experience this has to be. If God has ever breathed the words, “Well done thou good and faithful servant” it is now. When my grandparents arrived in this country, there were only a handful of churches and a few hundred Christians. As of today, there are 63 churches in the Boromo area alone! There are churches in Ouagadougou and some of the other large cities that seat thousands. A recently initiated convention center outside Ouaga regularly draws tens of thousands of believers. If my grandparents had not obeyed the call of God and left all they knew for this strange and often terrifying land, then history itself, at least for this African country, would be dramatically different. Each and every village we visit hammers the point further home for me. As my camera snaps away at the beautiful people, I realize without a doubt that I am not the only grandchild of Herman and Viola Engelgau in this country.

* * *

The last morning before we were to leave Boromo, my mother and I rose before the rest of the world, slipped into our clothes, and stole out into the dark, cool morning. Sitting together on an old well my grandfather blasted from the earth, we watch the sun rise amid birdsong. My mother is crying. We stroll around the property and at one point my mother drops to a knee, produces an empty film container from the folds of her dress and scoops a palm full of the courtyard into it.

“I so love these people.” She says as she presses the lid into place. “I belong here. This is where I belong.”

As we pull away later that morning, the tears are multiplied. My grandparents realize this is the last time they will see this house, these people. “This is harder than I the first time I left,” my grandfather admits.

After leaving Boromo following three terms, my grandfather was promoted to field chairman, and asked to head the Ouaga mission. For the last two terms of their mission experience they spent their days in the city (though a drastically smaller entity than that in which we now find ourselves). While no less a blessing, the switch from Boromo back to Ouagadougou is nonetheless a difficult one. The differences between urban and rural life clash within my head as I once again find myself on the frenzied streets of Burkina’s capitol. Even poverty looks different from here. In the bush villages, people are poor but self-sufficient. They do not know the things they lack and in many cases they do not care to. Materialism of that sort has yet to seep into their thinking. Here in Ouaga, there is a much more sordid, pervasive poverty. In one year, the average Burkina wage is just shy of one hundred U.S. dollars. This is the kind of poverty that wakes in the morning along side a person and asks sinisterly, “Where is your hope? What are you even waking up for? What is the point of your existence other than to sit here day after day, selling the same useless trinkets until you are sick and twisted with age?”

But the church is as alive here as it is in the bush and making just as much of an impact. We visit schools run by the church for primary, secondary, and religious education. In addition, we tour technical schools and schools for delinquent children. Everywhere we look, from the inside of churches that themselves have sent out missionaries, to the streets of the cities in which they reside, God’s love is being poured out daily in very real, tangible, immediate ways.

I was amazed at the caliber of people I met every day that I was in Africa. I asked myself once what it was going to take to bring Africa out of the dark ages of the past and into the light of the future. The answer was around me every day, brushing my shoulders. “Africa is in good hands,” my grandmother commented upon leaving one of the churches. Indeed it is. And how proud must be the parents of some of these young leaders—to have gone from a mud hut to pastoring a church of thousands in one generation. It makes one thrilled at the prospect of checking on this place again to see what the current crop of children will rise up to become. The possibilities are limitless.

Traveling to Boromo was nothing like it was when my grandparents lived here. They relate stories of a half-day of travel on a wide dirt road, chocking on the red dirt that coated every surface of thier car, clothes and bodies. Our trip today takes barely over two hours and is sped along by a newly installed paved road that finds my grandparents shaking their heads in astonishment. The ground here is a bright red contrasted sharply with the thick green of the vegetation that flashes past our car in dense emerald smudges. This is the rainy season and the face Burkina is showing the world is an utterly deceptive one to those who do not understand the African climate. Mere months from now this green will be a distant memory, as will the leaves and foliage that clothe every tree. With unbearably stifling temperatures, the water of the rainy season will evaporate into the burnt browns of the dry season and the African bush will put on the face of a thing more dead than alive. I, for one, am glad I came when I did.

Memories, poignant and as starkly defined as burnished marble flit about my family like so many invisible butterflies as we pull up to the house my grandfather built and in which they raised their children. I find myself snapping pictures of them like some sort of insensitive photojournalist, capturing the moments when they cross the thresholds of the various rooms and the tears soak through and overwhelm them. There will be many tears in the next few days as we amble along the old paths and ingest sights not seen or perhaps even thought of in three decades.

* * *

A parade of people. This is the only possible way to describe the wave upon wave of visitors that came to greet my grandparents and mother. Every day, from shortly after sunrise, to well after dark, a steady stream of visitors fed its way into the house like a human tributary. There are very few private moments on this trip and even fewer to catch one's breath. The people come from near and far, staying for only a few moments or for several days. But they all come with one intent—to fall on the neck of “Papa” and “Madam” and “little Charlene,” to kiss and hold them and let their tears mingle as their lives once did. Pastors and bible-school graduates, old cooks, drivers and groundskeepers, masons and iron-workers, church layman and government officials, Christian and Muslim--they all come.

I watch this with the odd perspective of a well-informed fly on the wall. My grandparents seem charged with electricity and more in their element than I have ever seen them before. It is strangely disconcerting and equally compelling to watch your family chatter way in a language far more foreign than any taught on western campuses and one in which I have only heard when there was a need to secretly converse about that year’s Christmas presents. “Don’t you know,” I am told later, “they speak More in heaven!”

The visitors to the house (still in use by French missionaries now in Paris for medical furlough) are a marvelously beautiful bunch. There is no smile in the world at all more beautiful than that made when pearly white teeth break open on deep, black African skin. Tribal scars line and swirl their faces. Melodic voices resonate through teeth chiseled to fine points. The women move with a deliberate and graceful poise. It is of little surprise they can walk (and even ride) with such large bundles atop their heads. The children bear a subservience to their elders that is equal parts refreshing and maddening. They embrace us, covering us with a multitude of kisses and grasp our hands repeatedly while simultaneously chirping contentedly. Their face, beaming, cannot hide the joy of the Lord.

“My heart is full.” One visitor exclaims.

“Not as full as ours,” my grandmother replies.

That Sunday, sitting in the church my grandfather constructed and ministered in, we are treated to a service that lasts over five hours. With the sounds of African drums and voices still ringing in our ears, I discover first-hand just how loved my grandparents really are. Packed to capacity, the crowds line the outside of the church, faces peering intently through the slated windows for any glimpse inside.

Eloquent tributes (“They loved us with their hearts, not just their teeth”) and lavish gifts are presented and when my grandmother stands to address the gathering, it is with a broken voice that she announces, “Today, I have tasted heaven.”

Later in the trip, after a similar evening, my grandfather sits silently in the restroom for a long time. When my grandmother asks him through the door if he’s ok, he replies, “I’m just in here bursting my buttons. I’ve never felt so much honor and reverence in my life.”

“Your grandfather always stands up so much straighter here.” My grandmother confides to me afterwards.

* * *

I love the sound of my grandfather’s voice. He has a James Earl Jones quality which, what it lacks is depth of tone, it matches in power and inflection. Be I boy or man, there are few better moments I have experienced than sitting at my grandparent's Portland breakfast table, full on homemade toast and jelly, listening to my grandfather read devotions.

Nearly 80, hunched with time and plagued by pain in his hands, hips and knees, my grandfather is no longer the man I see in the old slides of Africa he loves to pull from the attic every Christmas visit. He cannot move as fast or stand as straight, but I realize a hundred times over, as I stand beside him, taller by nearly two feet, that my grandfather is a giant of a man.

Listening to my grandfather preach several times this trip, I am painfully reminded that it may be one of my last times to be so honored. I smile to myself as he confuses the languages of his sermon, vacillating between English, More and French without noticing he’s made the switch. If a grandson can be more proud of his grandparents than I am, I cannot see how. They are too humble to swell with the pride I allowed myself to be infused with on this trip. Watching my grandparents together (she is ramrod straight, walks more briskly than any 18-year-old, and seems in every way a polar opposite of her husband) I was daily overcome with the realization that my grandparents are truly great human beings who have done truly great things in this world. I could never have comprehended to what degree that was true had I not “tagged along” on this trip.

Using Boromo as our base camp of sorts, we journeyed daily to numerous villages that lay in the outlying provinces. Villages with names like Oury, Pompoi, and Bagesi. In each, hundreds of people swarmed from their huts and houses to greet us as we pulled up to the local church building. My grandfather had built nearly every one. The small blue plaque above each entryway denoting the church as of the “Assemblees de Dieu” had become so very familiar that it prompted one person to comment that the three things you see most in Burkina these days are “Blue jeans, Coke-a-Cola, and Assemblies of God churches.”

Nearly every church is packed to overflowing. At many villages, larger buildings are being constructed a stone's throw away. At Ouhabo, we visit with the local congregation as they toil under the hot sun. Half naked women slap mixtures of mud and tar over sun-dried mud bricks and smear it flat. Behind them, several men stomp in a pit of muck, preparing the next batch. The roof is the only thing they cannot provide. The rains make anything other than a metal roof impossible and such materials are nearly unattainable or unfeaisibly expensive. They build the church anyway, confidant that God will provide.

Lunch comes in the form of delicious peanut and chicken sauces poured overtop heaping helpings of white rice. Those who believe that the only reason for solid food in the first place is so that there is something on which to put sauce will love the food in Burkina--everything comes with sauce. A stir of the saucepot reminds one of the more adventuresome nature of the trip as chicken feet and heads bob to the surface. Each visit brought more gifts--from clothing, carved sculptures, leather goods, guinea-hen eggs and armloads of struggling chickens that would find their way noisily to the cab of the pickup each day and tastily to our dinner plates each night. Utterly without material possessions, these people gave all that they had; more than they could afford to give, but they gave it willingly, rejoicingly. Without knowing where their next meal was coming from, they happily presented us with more than we could ever hope to eat.

“Africa is not about sights, it is about people,” said Benjamin Yanogo, a local pastor who was to be our trip’s chaffer, translator, horticulturist and in the end, our dearest of friends. Merely one in an utterly magnificent family, he will knit himself to our hearts in the short weeks we are there like no other. “Here, there are no real monuments to see, only life itself.”

At one of the churches we visit, a man opens his Bible and withdraws a bookmark, yellowed with age. On it, my grandparents smile at me, practically as young as I am now. Not Grampa and Grama, but Hermie and Vi, youthful and virile. The bookmark has been there, tucked away safely in the folds of those pages for half a century.

And it hits me—what a life-validating trip! What an utterly authenticating experience this has to be. If God has ever breathed the words, “Well done thou good and faithful servant” it is now. When my grandparents arrived in this country, there were only a handful of churches and a few hundred Christians. As of today, there are 63 churches in the Boromo area alone! There are churches in Ouagadougou and some of the other large cities that seat thousands. A recently initiated convention center outside Ouaga regularly draws tens of thousands of believers. If my grandparents had not obeyed the call of God and left all they knew for this strange and often terrifying land, then history itself, at least for this African country, would be dramatically different. Each and every village we visit hammers the point further home for me. As my camera snaps away at the beautiful people, I realize without a doubt that I am not the only grandchild of Herman and Viola Engelgau in this country.

* * *

The last morning before we were to leave Boromo, my mother and I rose before the rest of the world, slipped into our clothes, and stole out into the dark, cool morning. Sitting together on an old well my grandfather blasted from the earth, we watch the sun rise amid birdsong. My mother is crying. We stroll around the property and at one point my mother drops to a knee, produces an empty film container from the folds of her dress and scoops a palm full of the courtyard into it.

“I so love these people.” She says as she presses the lid into place. “I belong here. This is where I belong.”

As we pull away later that morning, the tears are multiplied. My grandparents realize this is the last time they will see this house, these people. “This is harder than I the first time I left,” my grandfather admits.

After leaving Boromo following three terms, my grandfather was promoted to field chairman, and asked to head the Ouaga mission. For the last two terms of their mission experience they spent their days in the city (though a drastically smaller entity than that in which we now find ourselves). While no less a blessing, the switch from Boromo back to Ouagadougou is nonetheless a difficult one. The differences between urban and rural life clash within my head as I once again find myself on the frenzied streets of Burkina’s capitol. Even poverty looks different from here. In the bush villages, people are poor but self-sufficient. They do not know the things they lack and in many cases they do not care to. Materialism of that sort has yet to seep into their thinking. Here in Ouaga, there is a much more sordid, pervasive poverty. In one year, the average Burkina wage is just shy of one hundred U.S. dollars. This is the kind of poverty that wakes in the morning along side a person and asks sinisterly, “Where is your hope? What are you even waking up for? What is the point of your existence other than to sit here day after day, selling the same useless trinkets until you are sick and twisted with age?”

But the church is as alive here as it is in the bush and making just as much of an impact. We visit schools run by the church for primary, secondary, and religious education. In addition, we tour technical schools and schools for delinquent children. Everywhere we look, from the inside of churches that themselves have sent out missionaries, to the streets of the cities in which they reside, God’s love is being poured out daily in very real, tangible, immediate ways.

I was amazed at the caliber of people I met every day that I was in Africa. I asked myself once what it was going to take to bring Africa out of the dark ages of the past and into the light of the future. The answer was around me every day, brushing my shoulders. “Africa is in good hands,” my grandmother commented upon leaving one of the churches. Indeed it is. And how proud must be the parents of some of these young leaders—to have gone from a mud hut to pastoring a church of thousands in one generation. It makes one thrilled at the prospect of checking on this place again to see what the current crop of children will rise up to become. The possibilities are limitless.

2 Comments:

All I can say is...WOW. WOW, WOW, WOW.

To see Africa through your words and your pics is amazing and makes me wish I were going to Kenya this summer with our team.

WOW.

That's funny Brandon. I still have a copy of those. It's some of your best writing, and I still think you and National Geographic would be perfect for each other.

Post a Comment

<< Home