A meeting of minds...

Making Sci. Fi. Cool Again…While the 1950s produced some fascinating and thought-provoking science fiction, it was largely bleak and fatalistic. Facing down Soviet missiles at every turn, Cold War America’s favorite escapist genre became a way to deal with the angst and terror many Americans felt when they looked at the world around them. Many of these films presented humans as victims at the mercy of baffling, hostile and evil otherworldly forces. Sometimes these forces attacked outright, leveling human cities and obliterating our way of life. Other times they lay low on our planet, slowly assimilating our minds, bodies and territories. With alien forces as barely disguised metaphors for Communism, these allegorical science fiction films reflected Americans’ collective unconscious.

From

The Thing From Another World (1951) about an alien killing off scientists on an Artic research station, to

Earth vs. the Flying Saucers (1956) in which Washington D.C. and all vestiges of democracy are laid waste by marauding alien space-craft, to

Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1956) which reflects the post-McCarthy era in which anyone might be a Red Commie by presenting a sleepy town in which parasitic alien seed pods duplicate the town's inhabitants, transforming them into emotionless, mindless automatons--science fiction was always deeper than many who laughed it its (often-laughable) special effects gave it credit for.

(Robert Wise’s

The Day the Earth Stood Still (1951) is one of the few exceptions, a film about a benevolent, Christ-like alien emissary who comes to Earth to try to prevent us from destroying ourselves through nuclear war. Naturally, we try to blow him up.)

While the 1960’s was the decade in which man first stepped foot on the moon, the momentous events barely made a dent in Hollywood sci. fi. philosophy. The films, if anything, got bleaker.

The Andromida Strain (1969) tells of a world in which humans are nearly undone by an alien force too small to even see with the naked eye. In Stanley Kubrick’s monumental

2001 (1968) humanity is so bereft of awe and emotion that space cannot even captivate us any longer, while

Marooned (1969) and

Robinson Crusoe on Mars (1964) showed space as a lonely and empty void.

As society began to change, science fiction films changed with it. They began to reflect the dark and dirty times our country was going through. Far from uplifting, the films of the 60s and 70s were apocalyptic stories –

Planet of the Apes (throughout the 70s),

Silent Running (1971)—which capitalized on the youths’ cynicism, distrust of authority and uncertainty about the future.

As America headed into the 70s, the country was mired in the present—Vietnam was splintering the country in two, stagnation was crippling the economy, rising oil prices were taking a bite out of ordinary Americans’ lives (any of this sound familiar!?), President Nixon resigned in disgrace, further abolishing the belief in great leaders and heroes—and the social and political upheaval was omni-present in all forms of entertainment.

Then came 1977.

In May, a behemoth of a movie hit movie screens and caused a cataclysmic reaction in the film industry. An epic story of good vs. evil set with mythological archetypes and boasting special effects the world could not even fathom,

Star Wars represented a massive break-through in the world of science fiction. Sure, there were evil monsters here too, but there were also courageous men and women of inestimable good willing to do battle with the evil for the salvation of the galaxy. A jaded and world-weary public devoured it.

Later that year, an only slightly less iconographic and popular movie hit theater screens. It was Steven Spielberg’s

Close Encounters of the Third Kind, a magical, beguiling and transcendant look at a first contact event between humans and aliens. The thing that made

Close Encounters so very revolutionary was its optimistic, even loving portrayal of our alien visitors. These were not monsters come to destroy us, but benevolent beings who wanted nothing more than for us to communicate and learn from one another.

Spielberg sits with "Close Encounters" child star, Cary Guffey.

A few years later, in 1981, Spielberg made aliens the focus of yet another film, this one the dearly-beloved

E.T., The Extra-Terrestrial. Immensely popular, the magical film about the relationship between a stranded alien and an awkward boy used Biblical imagery to convey the idea that alien life forms wished us nothing but peace, harmony and relationship.

Steven Spielberg directs 10-year-old Henry Thomas in 1982's "E.T."

Spielberg (and Lucas) had done something no one else could have, or perhaps desired, to do. They had made science fiction cool again. And they had done so by telling us that “the other” was not to be feared. That life is out there and it desires friendship with the people of Earth. That, though we may look different and be from different worlds, we are all, in our hearts and souls, very much the same. The future, it was suggested, is very bright indeed.

War of the Worlds Through Time…When English writer H.G. Wells penned “The War of the Worlds” in 1898, the book upon which a radio broadcast, two films and a television series would be based, he did so not for purposes of entertainment, but to condemn his country’s colonial imperialism. Great Britain, the empire on which the sun never set, was the sole superpower of its day and had been for as long as anyone could remember. A subversive novel, the embattled humans represented the dodo, the bison, the aboriginal tribes of Tasmania, and other now nearly extinct groups, while the malevolent Martians stood in place of the British. Wells invited a sort of national self-reflection as to England’s role in the raping, pillaging, and careless destruction of the world by inviting his readers to feel what it was like to live beneath the cruel domination of a far superior and advanced civilization.

Since its original publication, “War of the Worlds” has always been associated with one or another allegory far greater than the story itself, all occurring at a time of great unease in the history.

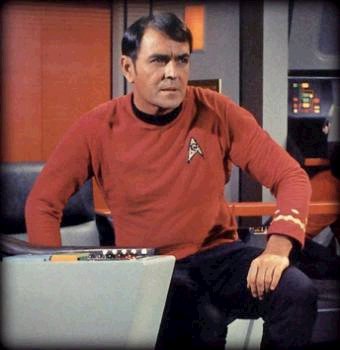

Orson Wells prepares for his infamous "War of the Worlds" broadcast.

In 1938, Orson Welles caused a massive, nation-wide panic when he and his radio play about Martian invaders was taken by many to be a actual news report. Less than a year later the Nazi invaders rolled over Poland and began World War II.

"War of the Worlds," Cold-War style.

In 1953, in the middle of the Cold War, George Pal made

War of the Worlds into a film, presenting the besieged Americans as stout, heroic, God-fearing victims of an unprovoked and presumably Soviet-style attack.

Spielberg on the set of "War of the Worlds" with star, Tom Cruise.

And now, in 2005, Steven Spielberg has remade the now-familiar story into a film to reflect our post-9/11 sensibilities.

War of the Worlds—Spielberg StyleWar of the Worlds is not a good film. There, I’ve said it.

It’s not that it isn’t well crafted or that it doesn’t have astonishing special effects. It is and it does. But for all that it has going for it, the latest rendition of the popular story is flat, uninspired, disturbing and unfulfilling.

This is Spielberg at his unabashedly commercial worst—bland, unimaginative, and more interested in his bang than his brain. More so than any other Spielberg film, it is impossible to watch

War of the Worlds without thinking of his other movies:

Ominous clouds billowing toward our heroes are straight out of

Close Encounters. A scene in which an alien probe (which looks remarkably like the head of

E.T.) searches a basement for human prey perfectly mirrors a scene in

Jurassic Park where a raptor searchers for the hiding children, or

Minority Report where a robotic scout is looking for a fugitive. The tripods make a legitimately terrifying bellow before opening fire on their victims, but for a moment, you realize it is the same initial sound that began the musical five-note sentence in

Close Encounters. The cages in which the humans are stored as food under the heads of the "tripods" recall similar devices in

A.I. I could go on, but you get the idea.

The film is not without its deeper themes, but it explores them so clumsily and so schizophrenically that one cannot tell what the film is for and what it is against. While the screenwriters said that they were making an anti-war movie, and specifically an anti-Iraq war movie, the execution of these ideas is too disjointed to be coherent.

On the one hand, the film can be seen in light of the original manuscript, injecting the nationality of the primary viewership into the part not of the oppressed, but of the oppressor. Many parts in the film seem to suggest this:

• Before the attacks change the planet’s priorities, Cruise’s son, Robbie is supposed to be working on a report about the French occupation of Algeria. A historically botched occupation in which the far superior European force was pushed out of North Africa by a smaller, more dedicated insurgency, there is little doubt as to what Robbie’s report is supposed to symbolize.

• Later, the isolationist Ogolsby tells Cruise that he has no doubt that humanity will eventually prevail, because, in any conflict, the occupying country is never strong or resolved enough to stick out a full scale occupation in the face of a retaliatory populace.

• When Cruise and his kids arrive at a ferry landing in the only working car, a massive crowd gathers round the vehicle. It isn’t long before mob mentality takes over and the crowd attacks the car and the people inside, leaving, in the end, several dead bodies as a result. The idea of mob rule in America and the “Kill ‘em all and let God sort them out” attitude some see it having generated, can easily be read into this scene.

While Spielberg and his screenwriters seem to be making a statement about America’s precarious role in world affairs, the film simultaneously and intentionally evokes the images and feelings of that fateful September morning in 2001, going so far as to muddy the cinematic waters and compare the alien attack to the terrorist attack.

• When the tripod machines begin attacking the citizenry in the streets, vaporizing their bodies with frightening death rays, they instantly combust, spraying human ash into the air that then coats the survivors and brings to mind the dust covered faces of the World Trade Center collapse.

• Driving from the scene of the initial attack and seeing carnage sweep behind them, Cruise’s daughter, played by Dakota Fanning, screams, “Is it the terrorists?” (These leads to a funny exchange between Cruise and his son when Cruise replies, “No…this came from somewhere else.” “You mean Europe?” Robbie asks).

• Later, hiding in a basement, Cruise and company hear what they think is an attack outside. Only later do they discover that a gigantic passenger jet has crashed and now litters the suburban street in gnarled, twisted pieces of wreckage. The allusions to the hijacked planes or even the plane that plummeted into a Queens neighborhood two months after the terrorist attack, seem clear.

Beyond the schizophrenic political sub-text,

War of the Worlds just doesn’t make sense, period. It has plot holes large enough to fly a spaceship through.

The attack is malevolent, destructive, and pointless. For a race that has been “planning this for a million years” the aliens have gone to a lot of trouble to invade Earth without any apparent reason and with a fatally flawed strategy.

Some friends have delighted in the fact that the aliens’ intensions were never spelled out and while I didn’t expect a “press release announcing their plans for world domination” as Roger Ebert wrote in his review of the film, I was looking for a few more answers to their behavior. While I normally appreciate ambiguity and mystery, the fact that the aliens’ motives were not spelled out did not make them scarier, it made the script poorer.

They zap some human beings but collect others. Why? They suck the blood out of their victim's bodies and spray it over the landscape. Why? If they truly did deposit their machines deep beneath our planet’s surface millions of years ago, what purpose did it serve? Did they feel they needed such massive fighting machines to take over a world populated by evolutionary backward monkeys? Why not just take over the planet then? And why didn’t a civilization as advanced as this one (and with millions of years of even more technological progression) do a bit more research on the conditions on this planet before launching its invasion force?

The implausibilities hamstring the film and lead to a resolution of the war that, while true to the original novel, is handled in such a way that smacks of a contrived

Deus ex Machina conclusion. The end of the film is abrupt, predictable, Hollywood sentimental, convenient and thoroughly unsatisfying.

And on top of all this, while Spielberg begins with familiar territory we've seen before--a broken home, a dysfunctional and absent father, bright but awkward kids--he doesn’t develop them beyond their cardboard dimensions. The human characters are disappointingly one-dimensional (Spielberg seems to have lost his ability to draw magical performances from children) while his choice of a gratuitous and flagrantly unnecessary scene where we view the aliens cripples the film. Spielberg should know better. If Hitchcock taught us anything, it’s that what you don’t see is far scarier than what you do see. (M. Night Shyamalan knew this in

Signs, a far superior alien invasion movie from a far superior story-teller who may very well be wearing the mantle Spielberg seems to have shrugged from his shoulders.)

This isn’t to say that the film doesn’t have some redeeming values. The special effects are magnificent. The alien tripodal machines are terrifying and very believable. And there are moments of genius, the best being when Cruise, torn between saving one or the other of his children, must let his son go. The way he lets his hands glide across every inch of his son’s retreating body is breath-taking.

Where, Oh Where Has Steven Spielberg Gone?And now—FINALLY—we come to the point of this blog.

I intentionally pulled

Close Encounters of the Third Kind from my shelf and watched it the day before I went to see

War of the Worlds. I had a premonition that I would walk out of the theater disappointed. Shortly after the viewing, I sat down to my copy of

E.T. You see, I had to renew my faith.

I miss Steven Spielberg.

I’m not saying the director is not allowed to change, or mature, or grow more cynical with age. But what I am saying is that I miss the youthful vibrancy, childlike zeal, and optimistic idealism that not only defined all of his early films, but several decades of entertainment as well. I miss the Spielberg before he thought he was Stanley Kubrick. I miss the Spielberg that rejoiced in the unknown and took great pleasure in the world’s many mysteries.

The Spielberg of the 21st century is like the priest in Ingmar Bergman’s haunting

Winter Light who has lost his way and his faith and yet continues to preach what he no longer believes in until it all becomes too much for him and he wants nothing more than to renounce everything he once stood for. And as a parishioner, standing on the outside, used to being fed communion by him, it is a sad and perhaps even tragic thing to witness.

Yes,

War of the Worlds contains some sensational sights. But it lacks the zest and joyous energy we expect from a Steven Spielberg picture. It lacks idealistic integrity. And it lacks courage. Was the march of years all it took to do this? Was a terrorist attack all it took to alter your world-view, Steven? What happened to the sense of wonder celebrated in

Close Encounters of the Third Kind? What happened to the dazzling imagination of

E.T.?

How can the same man who revolutionized science fiction films and a society along with it now tell Empire magazine, “I did have fun making mean-spirited aliens that only want to do harm. That was actually one of the biggest kicks I got making

War of the Worlds”?

War of the Worlds just may represent the bleakest view of humanity that has ever come out in one of Spielberg's films.

Is this the future to which we have to look forward? As our country sinks toward another age of war, recession, fear and pessimism, has Spielberg become the very thing he once supplanted? Will Hollywood once again glory in bleak stories told to despairing viewers in a dingy world? Is the circle unbreakable?

We must wait and see.

For now, it seems Spielberg has traded wonder for terror, awe for gore, innocence for cynicism, optimism for fatalism, day-dreams for nightmares, Peter Pan for the Brothers Grimm.

And the cinema is poorer for it. And so are you and I.