TELESCOPE FAITH: Part I

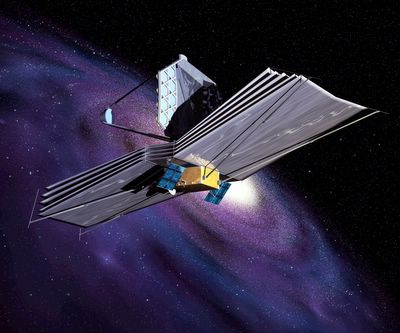

JWST

I’m not quite sure why I am writing this other than a need from someplace deep within me to do so. To explain myself. Sort of. Not because I need to justify my actions, but because sometimes you have to get something that’s been gnawing at you off your chest before it bores a hole all the way through you. I am worried that it might come across angry and bitter when most of those emotions long ago gave way to indifference or even amusement. I am worried that some people might be offended when, in fact, it is really a culture I am addressing and not any specific people or institutions. Some may find my musings and impressions scurrilous while many others, I know (from having spoken with you), will find them eerily on target. I guess if this blog is a sort of story of progression, the story has to have a beginning, has to have a reason for the protagonist to take the fork in the road rather than continue on straight ahead. This is the beginning of that story. Sort of.

I had lots of time on my hands over the chilly, April weekend. The video production company for which I work was charged with recording the construction of a life-sized replica of a satellite telescope in the middle of a posh hotel parking lot for a big space symposium that happens here every year. My job—baby-sit a digital time-lapse camera snapping away every few seconds for well over 10 hours on a nearby rooftop.

It wasn't a hard job. Mind-numbingly boring actually. But spend a full day on a roof, exposed to bitter winds, your pea-coat collar wrapped tightly around your neck and a wool cap pulled snuggly down around your ears, your only intellectual exercise glancing occasionally at a computer screen and your mind begins taking you on some odd tangents. I found myself comparing my life to the metallic behemoth being assembled ever-so-precisely (and ever-so-slowly) beneath me.

Envisioned to peer into the heavens at greater distances than humankind has ever looked before, the James Webb Space Telescope is designed to observe the formation of the first stars and the evolution of galaxies in the universe billions of years ago. To do this, the JWST will employ a 6.5-meter aperture primary mirror, comprised of 18 hexagonal-shaped segments. The massive mirror, seven times that of Hubble’s, gives it the light-collecting sensitivity to see objects 400 times fainter than those currently observed by ground- and space-based telescopes. At the heart of all of its circuitry, cables and computer chips is a very human question: Where did we come from and by extension, where are we going?

I’m like that too. The JWST is being sent into deep space to try to discover what’s out there. I too am constantly sending out spiritual feelers, my own religious mirrors set in an attempt to glean whatever distant and ancient mysteries I can about the origins of life and human purpose. Sometimes staggering discoveries are made. Telescopes capture luminescent images of starry nebula or spiral galaxies. Or my soul captures the pulse of God, and for a moment, I glimpse what and who is truly important. Often times, however, it is only a cold, dark, listless search bolstered by the faith in the evidence (or the God) that led to the search in the first place.

When I wasn’t personifying myself in hunks of metal, I found I had plenty of time to read. My book of choice was Patton Dodd’s, “My Faith So Far.” My wife read it first and found it fascinating. She grew up with Patton, knew him from the megachurch he so voluptuously describes and cringes at the things that made him put pen to paper in the first place. Still, she suggested, this might be more a personal memoir than something with more widespread appeal.

Patton Dodd grew up in a good Christian home with good Christian parents. And like so many kids in his position, he rebelled, fell away from the faith, and indulged in sex, drugs, and rock & roll. The cliché.

But during his senior year of high school, he found himself accompanying his sister to a charismatic megachurch here in Colorado Springs ("The exterior of the church looks like a Wal-Mart with half a paint job: a blue-and-light-blue concrete box surrounded by acres of parking"), and there, to the surprise of everyone, himself included, he responded to the altar call. Evoking the evangelical liturgy, he confessed his sins and prayed for repentance, signed a card where he indicated he wanted to "accept salvation" and "renew my commitment to Jesus Christ" and walked out of the church, ready "to begin my life anew. Voila."

Dodd does his best to become a fanatically "evangelical, Bible-believing, chest-pounding Christian" grounding his new identity in the sort of fervent absolutes and unquestioning faith that characterize a new believer’s faith. It doesn’t help matters that he still wants to drink, do drugs, screw and go around with girls that do. And he often does.

Realizing he can no longer live life like he used to, Dodd ratchets his resolve, exchanging pot smoking for worship dancing, gives up MTV for banal Christian pop, and enrolls at Oral Roberts University, a Christian college that he sees as the ultimate way of ridding himself of the snares of the world and submerging himself in a culture that will have all the answers.

However, he soon finds himself ill at ease with the Christians around him as well as with the cloying superficiality of the Christian subculture. He is bewildered when a friend suggests that God-fearing Christians shouldn't study literature. He is bamboozled when his Journalism professor doesn’t mention a word about his subject for weeks and chooses instead to muse on prayer. He is flummoxed by his university's founder’s claim that unless he is given millions of dollars soon, God will kill him. He is troubled by the name-it-and-claim-it school of prayer his school embraces. (One young prayer warrior entreats, "Father, you know I need a new truck, so right now I just claim a Toyota 4X4, 3.4 liter, six-cylinder, extended cab — red with white trim. I need low payments and affordable insurance. I just claim these things in Jesus' name").

It’s a wonder he didn’t chuck the whole Christian thing right there.

But this isn’t a story of conversion. It is a story of what comes after. The dateable, spiritual birthday if you will, isn’t the most important thing in Dodd’s life or the narrative, but the turning point at which he begins to truly realize what his new faith requires of him and how he will deal with it. This period of faithful doubt and doubt-filled faith marks the crux of the book as Dodd struggles to reconcile the Sunday school version of Christianity--the sort spoon fed to new believers--with the more adult, controversial and even paradoxical truth of a more mature journey. It is a time of deep questions and even deeper doubts, told in dynamic contradiction: conversion and confusion, acceptance and rejection, spiritual highs and psychological lows. With painstaking transparency, Dodd tries to parley a relationship with his faith at odds with the cultural trappings that so gaudily and tawdrily clothe it.

But here’s the thing. Whether it has mainstream appeal is certainly arguable. I think it does. Either way, it doesn’t really matter to me because it certainly has personal appeal.

You see, Dodd’s story is my story.

to be continued...

1 Comments:

Interesting story...

There are a lot of aspects of my journey that resinate with your story.

I think that this might be a good topic for our next monthly lunch talk...

Post a Comment

<< Home