Thursday, March 31, 2005

I've been wanting to establish a portfolio webpage of some of my photography for some time. I'm finally getting around to doing it. To check it out, click on the title link above and be sure to check back over the next few weeks as I have many more countries and pictures yet to add. Enjoy.

Wednesday, March 30, 2005

MARCH BOOK REVIEW: "Searching For God Knows What" by Donald Miller PART III

In this way, the chief difference between morality in a relational context to Jesus and morality in the context of the lifeboat is that one system works for people and the other against them.

It is obvious when reading Scripture that what you and I commonly think of as morality is thin in definition. Some Christians, when considering immorality in culture, consider two issues: abortion and gay marriage.

Moral ideas presented in the New Testament, and even from the mouth of Christ, however, involve loving our neighbors, being one in the bond of peace, loving our enemies, taking care of our own business before we judge somebody else, forgiving debts even as we have been forgiven, speaking in truth and love else we sound like clanging cymbals (turn on Fox News to hear what clanging cymbals sound like), and protecting the beauty of sex and marriage.

Morality, then becomes the bond, the glue that holds our families together, our communities together, and our churches together, and most important, builds intimacy with Christ. Morality, in the context of a relationship with Jesus, becomes the voice of love to a confused community, the voice of reason and calm in a loud argument, the voice of life in a world of walking dead, the voice of Christ in a sea of self-hated.

* * *

The trick Satan has played on us involving his spin on morality has not gone unnoticed by those outside the church.

In his book “Lies and the Lying Liars Who Tell Them,” Al Franken included a provocative multi-page comic strip about a man named Supply-Side Jesus. In the strip, Supply-Side Jesus walks through the streets of Jerusalem stating that people should start businesses so they can employ the poor and should purchase exotic and expensive clothes and jewelry so their money will trickle into the economy and, eventfully, bring bread to the mouths of the starving.

In the comic, the disciples come to Supply-Side Jesus and say they want to feed the poor directly, but Supply-Side Jesus says no, that if you give money or food or water directly to the poor, you are only helping them in their laziness and increasing the welfare state. Eventually, Rome catches up with Supply-Side Jesus and, before an angry mob, Pontius Pilate asks the masses which man they want to crucify, Supply-Side Jesus or another man, who, in the comic, stands beside Pilate humbly, a disheveled and shadowy figure. The crowd chants they want to free Supply-Side Jesus because they like his philosophies, and they want to crucify this other man, the shadowy figure standing next to Pilate. Pilate tells the crowd this other man is innocent, that he has done no wrong, but the crowd refuses to listen and instead chants, “Crucify him, crucify him.” Pilate then lets Supply-Side Jesus go free, and orders the innocent man, whose name was Jesus of Nazareth, to be crucified.

I sat there reading the book at Horse Brass Pub in amazement. Here was Al Franken, a known liberal who often lambastes the conservative Christian right but who also, somehow, understands the difference between the Jesus the religious right worships and the Jesus presented in Scripture. One Jesus is understood through conservative economic theory, the other through the Gospels.

* * *

I recall watching a documentary detailing Muslim frustration, both domestic and Middle Eastern, with the perception that all Muslims subscribe to the sort of angry and dangerous extremism propagated by terrorist hijackers on September 11. “It was more than those planes that got hijacked,” one Muslim woman commented. “It was the nation of Islam. In the eyes of the world, they took our faith and flew it into those buildings. The damage may never be repaired.”

I wondered if the Christian faith had not been hijacked as well, hijacked by those same two issues: abortion and gay marriage. How did a spirituality such as Christianity, a spirituality that speaks of eternity, of a world without end, of forgiveness of sins and a mysterious union with the Godhead, come to be represented by a moralist agenda and a trickle-down economic theory? And more important, how did a man born of Eastern decent, a man who called Himself the Prince of Peace, a man whom the sacred writings describe eating with prostitutes and providing wine at weddings and healing the sick and ignoring any political plot, a man who wants us to turn the other cheek and give all our possessions if we are sued, become associated with—no, become the poster boy for—a Western moral and financial agenda communicated through the rhetoric of war and ignorant of the danger it is causing to a world living in poverty (emphasis mine).

My only answer is that Satan is crafty indeed.

I realize there are people reading this who will automatically dismiss me as a theological liberal, but I do not believe a person can take two issues from Scripture, those being abortion and gay marriage, and adhere to them as sins, then neglect much of the rest and call himself a fundamentalist or even a conservative. The person who believes the sum of morality involves gay marriage and abortion alone, and neglects health care and world trade and the environment and loving his neighbor and feeding the poor is, by definition, a theological liberal, because he takes what he wants from Scripture and ignores the rest (emphasis mine). Make no mistake, there is a lifeboat motive in play, a join a team and fight feeling that is roaming around like a lion, searching to destroy men’s souls.

* * *

The reason I bring this up is to plead with evangelicals to return to the sort of call Christ has given us, to obey Him and experience intimacy with Him through sharing our faith, loving our enemies, serving and feeding the poor and hungry directly, and to stop showing off about how moral we are and how that makes us better than other people. I assure you, once we leave the fight over our country’s future and enter the spiritual battle for the hearts and souls of the lost, the church will flourish, and the kingdom of God will grow. God is not in the business of brokering for power over a nation; He is in the business of loving the unloved and pulling sheep out of crags and bushes.

The greatest comfort I can feel in the middle of this is that Jesus did not lend Himself to war causes, to tax issues or political campaigns. For that matter, He did not lend Himself to raising money for education or stumping for affirmative action. It was as if He did not trust us to build a utopia (emphasis mine). He kept it very simple, in fact. Follow me, He said. I have no opinion about what color the paint should be in this prison. Follow me.

Is Jesus angry? Sometimes. Does He speak of sin and morality? Yes, quite frequently. Does the contemporary evangelical model of sin and morality reflect the teachings of Christ? As a flea is a part of a dog, but not to be confused with the dog itself. Is Jesus frustrated with sinners? Yes. Is He frustrated with religious zealots who use His Father’s name to build businesses or support agendas? He is violently frustrated. Is there a penalty to pay for rejecting Him? Yes, apart from Christ we will die and are dying. Does Jesus like liberals more than conservatives? He will be nobody’s flag.

* * *

I suspect any lack of love or feelings of anger we have toward the culture around us are not feelings that come from God, but rather our souls arising again to cast rocks at women caught in adultery (emphasis mine). We should not expect Christ to respond any differently to us than He did to the moralists of His day:

They dropped their stones and walked away, feeling ashamed that each of them had been proved a sinner, too. And Jesus went over to comfort the woman, telling her, “Go, and sin no more” (see John 8).

This concludes the chapter.

It is obvious when reading Scripture that what you and I commonly think of as morality is thin in definition. Some Christians, when considering immorality in culture, consider two issues: abortion and gay marriage.

Moral ideas presented in the New Testament, and even from the mouth of Christ, however, involve loving our neighbors, being one in the bond of peace, loving our enemies, taking care of our own business before we judge somebody else, forgiving debts even as we have been forgiven, speaking in truth and love else we sound like clanging cymbals (turn on Fox News to hear what clanging cymbals sound like), and protecting the beauty of sex and marriage.

Morality, then becomes the bond, the glue that holds our families together, our communities together, and our churches together, and most important, builds intimacy with Christ. Morality, in the context of a relationship with Jesus, becomes the voice of love to a confused community, the voice of reason and calm in a loud argument, the voice of life in a world of walking dead, the voice of Christ in a sea of self-hated.

* * *

The trick Satan has played on us involving his spin on morality has not gone unnoticed by those outside the church.

In his book “Lies and the Lying Liars Who Tell Them,” Al Franken included a provocative multi-page comic strip about a man named Supply-Side Jesus. In the strip, Supply-Side Jesus walks through the streets of Jerusalem stating that people should start businesses so they can employ the poor and should purchase exotic and expensive clothes and jewelry so their money will trickle into the economy and, eventfully, bring bread to the mouths of the starving.

In the comic, the disciples come to Supply-Side Jesus and say they want to feed the poor directly, but Supply-Side Jesus says no, that if you give money or food or water directly to the poor, you are only helping them in their laziness and increasing the welfare state. Eventually, Rome catches up with Supply-Side Jesus and, before an angry mob, Pontius Pilate asks the masses which man they want to crucify, Supply-Side Jesus or another man, who, in the comic, stands beside Pilate humbly, a disheveled and shadowy figure. The crowd chants they want to free Supply-Side Jesus because they like his philosophies, and they want to crucify this other man, the shadowy figure standing next to Pilate. Pilate tells the crowd this other man is innocent, that he has done no wrong, but the crowd refuses to listen and instead chants, “Crucify him, crucify him.” Pilate then lets Supply-Side Jesus go free, and orders the innocent man, whose name was Jesus of Nazareth, to be crucified.

I sat there reading the book at Horse Brass Pub in amazement. Here was Al Franken, a known liberal who often lambastes the conservative Christian right but who also, somehow, understands the difference between the Jesus the religious right worships and the Jesus presented in Scripture. One Jesus is understood through conservative economic theory, the other through the Gospels.

* * *

I recall watching a documentary detailing Muslim frustration, both domestic and Middle Eastern, with the perception that all Muslims subscribe to the sort of angry and dangerous extremism propagated by terrorist hijackers on September 11. “It was more than those planes that got hijacked,” one Muslim woman commented. “It was the nation of Islam. In the eyes of the world, they took our faith and flew it into those buildings. The damage may never be repaired.”

I wondered if the Christian faith had not been hijacked as well, hijacked by those same two issues: abortion and gay marriage. How did a spirituality such as Christianity, a spirituality that speaks of eternity, of a world without end, of forgiveness of sins and a mysterious union with the Godhead, come to be represented by a moralist agenda and a trickle-down economic theory? And more important, how did a man born of Eastern decent, a man who called Himself the Prince of Peace, a man whom the sacred writings describe eating with prostitutes and providing wine at weddings and healing the sick and ignoring any political plot, a man who wants us to turn the other cheek and give all our possessions if we are sued, become associated with—no, become the poster boy for—a Western moral and financial agenda communicated through the rhetoric of war and ignorant of the danger it is causing to a world living in poverty (emphasis mine).

My only answer is that Satan is crafty indeed.

I realize there are people reading this who will automatically dismiss me as a theological liberal, but I do not believe a person can take two issues from Scripture, those being abortion and gay marriage, and adhere to them as sins, then neglect much of the rest and call himself a fundamentalist or even a conservative. The person who believes the sum of morality involves gay marriage and abortion alone, and neglects health care and world trade and the environment and loving his neighbor and feeding the poor is, by definition, a theological liberal, because he takes what he wants from Scripture and ignores the rest (emphasis mine). Make no mistake, there is a lifeboat motive in play, a join a team and fight feeling that is roaming around like a lion, searching to destroy men’s souls.

* * *

The reason I bring this up is to plead with evangelicals to return to the sort of call Christ has given us, to obey Him and experience intimacy with Him through sharing our faith, loving our enemies, serving and feeding the poor and hungry directly, and to stop showing off about how moral we are and how that makes us better than other people. I assure you, once we leave the fight over our country’s future and enter the spiritual battle for the hearts and souls of the lost, the church will flourish, and the kingdom of God will grow. God is not in the business of brokering for power over a nation; He is in the business of loving the unloved and pulling sheep out of crags and bushes.

The greatest comfort I can feel in the middle of this is that Jesus did not lend Himself to war causes, to tax issues or political campaigns. For that matter, He did not lend Himself to raising money for education or stumping for affirmative action. It was as if He did not trust us to build a utopia (emphasis mine). He kept it very simple, in fact. Follow me, He said. I have no opinion about what color the paint should be in this prison. Follow me.

Is Jesus angry? Sometimes. Does He speak of sin and morality? Yes, quite frequently. Does the contemporary evangelical model of sin and morality reflect the teachings of Christ? As a flea is a part of a dog, but not to be confused with the dog itself. Is Jesus frustrated with sinners? Yes. Is He frustrated with religious zealots who use His Father’s name to build businesses or support agendas? He is violently frustrated. Is there a penalty to pay for rejecting Him? Yes, apart from Christ we will die and are dying. Does Jesus like liberals more than conservatives? He will be nobody’s flag.

* * *

I suspect any lack of love or feelings of anger we have toward the culture around us are not feelings that come from God, but rather our souls arising again to cast rocks at women caught in adultery (emphasis mine). We should not expect Christ to respond any differently to us than He did to the moralists of His day:

They dropped their stones and walked away, feeling ashamed that each of them had been proved a sinner, too. And Jesus went over to comfort the woman, telling her, “Go, and sin no more” (see John 8).

This concludes the chapter.

Tuesday, March 29, 2005

MARCH BOOK REVIEW: "Searching For God Knows What" by Donald Miller PART II

The hijacking of the concept of morality began, of course, when we reduced scripture to a formula and a love story to theology, and finally morality to rules. It is a very different thing to break a rule than it is to cheat on a lover. A person’s mind can do all sorts of things his heart would never let him do. If we think of God’s grace as a technicality, a theological precept, we can disobey without the slightest feeling of guilt, but if we think of God’s grace as a relational invitation, an outreach of love, we are pretty much jerks for belittling the gesture.

In this way, it isn’t only the moralist looking for a feeling of superiority who commits crimes against God, it is also those of us who react by doing what we want, claiming God’s grace. Neither view of morality connects behavior to a relational exchange with Jesus. When I run a stop sign, for example, I am breaking a law against a system of rules, but if I cheat on my wife, I have broken a law against a person. The first is impersonal; the latter is intensely personal.

* * *

There are a great many motives for morality, but in my mind they are less than noble. Morality for love’s sake, for the sake of God and the sake of others, seems more beautiful to me than morality for morality’s sake, morality to build a better nation here on earth, morality to protect our schools, morality as an identity for one of the parties in the culture, one of the identities in the lifeboat.

I confess, when I was young my mind rebelled form the standard evangelical mantra about morality. My rebellion was reactionary, to be sure. I can’t tell you how many times I have seen an evangelical leader on television talking about this culture war, about how we are being threatened by persons with an immoral agenda, and I can’t tell you how many sermons I have heard in which immoral pop stars or athletes or politicians have been denounced because of their shortcomings. Rarely, however, have I heard any of these ideas connected with the dominant message of Christ, a message of grace and forgiveness and a call to repentance. Rather, the moral message I had heard is often a message of bitterness and anger because OUR morality, OUR culture, is being taken over by people who disregard OUR ethical standards. None of it was connected, relationally, to God at all.

In this way, it has felt like one group in the lifeboat, the moral group, is at odds with another group, the immoral group, and the fight is about dominance in a fallen system rather than rescue from a fallen system. And I wonder, What good does it do to tell somebody to be moral so they can die fifty years later and, apparently, go to hell?

It makes me wonder, and even judge (confession) the motives of somebody who wages a culture war about morality without confessing their own immorality while pointing to the Christ who saved them, the Christ who wishes to rescue everybody.

Morality, in this way, can be a circus act, giving a person a feeling of superiority. And while morality is good, anything we do to get other people to clap, or anything that gives us a more prominent position in a sinking ship, runs the risk of replacing a humble nature pointed at Christ, who is our Redeemer. The biblical idea of morality is behavior associated with our relationship with Jesus, not bait for pride.

In fact, morality as a battle cry against a depraved culture is simply not a New Testament idea. Morality as a ramification of our spiritual union and relationship with Christ, however, is.

Paul said to the church at Rome that those who chose immorality would be given over to a depraved mind and their lives would be ruined, but in the next breath he said that because of his great love for lost people, he would be willing to go to hell and take God’s wrath upon himself. And he said this even about the Jews who were persecuting him. In other words, the call to morality is delivered through a changed and forgiven heart, a heart regenerated and delivered by Christ, desiring that all people repent and come to know Him. There is nothing here we can use in the lifeboat at all. The agenda is all God’s not ours, and God’s agenda is love.

I was thinking of Paul recently when I saw an evangelical leader on CNN talking about gay marriage. The evangelical leader agreed with the apostle Paul about homosexuality being a sin, but when it came time to express the kind of love Paul expressed for the lost, the kind of love that says, I would gladly take God’s wrath upon myself and go to hell for your sake, the evangelical leader sat in silence. Why? How can we say the rules Paul presented are true, but neglect the heart with which he communicated those rules?

My suspicion is the evangelical leader was able to do this because he had taken on the morality of God as an identity with which he was attempting to redeem himself to culture, and perhaps even to God. This is what the Pharisees did, and the same Satan tricks us with the same bait: justification through comparison. It’s an ugly trick, but continues to prove effective.

* * *

I was the guest on a radio show recently that was broadcast on a secular station, one of those conservative shows that paints Democrats as terrorists. The interviewer asked what I thought about the homosexuals who were trying to take over the country. I confess I was taken aback. I hadn’t realized that homosexuals were trying to take over the country.

“Which homosexuals are trying to take over the country?” I asked.

“You know,” the interviewer began, “the ones who want to take over Congress and the Senate.”

I paused for a while. “Well,” I said, “I’ve never met those guys and I don’t know who they are. The only homosexuals I’ve met are very kind people, some of whom have been beat up and spit on and harassed and, in fact, feel threatened by the religious right.”

Think about it. If you watch CNN all day and see extreme Muslims in the Middle East declaring war on America because they see us immoral, and then you read the paper the next day to find the exact same words spoken by evangelical leaders against the culture here in America, you’d be pretty scared. I’ve never heard of a homosexual group trying to take over the world, or for that matter the House or Senate, but I can point you to about fifty evangelical organizations who are trying to do exactly that (emphasis mine). I don’t know why. In my opinion, we should tell people about Jesus, not try to build some kind of temporary moral civilization here on earth. If you want that, move to Salt Lake City.

“And what is the name of this homosexual group that is trying to take over America?” I asked the host, somewhat angry at his ignorant misuse of war rhetoric.

“Well, I hear about them all the time,” he said, rather frustrated with me.

“If you hear about them all the time, what is the name of their organization?”

“Well, I don’t know right now. But they are there.”

“Can I list for you ten or so Christian organizations who are working to try to get more Christians in the House and the Senate?” I said to the host.

“Listen, I get your point,” he said.

“But I don’t think you do. Here is my position: As a Christian, I believe Jesus wants to reach out to people who are lost and, yes, immoral—immoral just like you and I are immoral; and declaring war against them and stirring up your listeners to the point of anger and giving them the feeling that their country, their families, and their lifestyles are being threatened is only hurting what Jesus is trying to do. This isn’t rocket science. If you declare war on somebody, you have to either handcuff them or kill them. That’s the only way to win. But if you want them to be forgiven by Christ, if you want them to live eternally in heaven with Jesus, then you have to love them. The choice is yours and my suspicion is you will be held responsible by God, a Judge who will know your motives. So go ahead and declare war in the name of a conservative agenda, but don’t do it in the name of God. That’s what militant Muslims are doing in the Middle East, and we don’t want that here.”

Amazingly, the host kept me on and allowed me to tell a story or two about interacting with supposed pagans in a compassionate exchange, and later even admitted that his idea that homosexuals were trying to take over the country had originated from an e-mail he had received, an e-mail he had long since thrown away but he thought perhaps from some kind of homosexual organization.

To be honest, I think most Christians, and this guy was definitely a Christian, want to love people and obey God but feel they have to wage a culture war. But this isn’t the case at all. Remember, we are not elbowing for power in the lifeboat. God’s kingdom isn’t here on earth. And I believe you will find Jesus in the hearts of even the most militant Christians, moving them to love people, and it is only their egos, and the voice of Satan, that cause them to demean the lost. What we must do in these instances is listen to our consciences, and allow Scripture to instruct us about morality and methodology, not just morality.

Paul was deceived when he persecuted Christians, thinking he was doing it to serve God, but God went to him, blinded him, and corrected his thinking. After this, Paul loved the people he had previously hated; he began to take the message of forgiveness to Jews and Gentiles, to male and to female, to pagans and prostitutes. At no point does he waste his time lobbying government for a moral agenda. Nobody in Scripture who knew and followed Jesus wasted their time with any of this; they built the church, they love people.

Once Paul switched positions, many people tried to kill him for talking about Jesus, but he never lifted a fist; he never declared war. In fact, in Athens, he was so appreciated by pagans who worshiped false idols, they invited him to speak about Jesus in an open forum. In America, this no longer happens. We are in the margins of society and so we have our own radio stations and television stations and bookstores. Our formulaic, propositional, lifeboat-territorial methodology has crippled the kingdom of God. We can learn a great deal from the apostles. Paul would go so far as to compliment the men of Athens, calling them “spiritual men” and quoting their poetry then telling them the God he knew was better for them, larger, stronger, and more alive than any of the stone idols they bowed down to. And many of the people in the audience followed him and had more questions. This would not have happened if Paul had labeled them as pagans and attacked them.

A moral message, a message of US versus THEM, overflowing in war rhetoric, never hindered the early message of grace, or repentance toward dead works and immorality in exchange for a love relationship with Christ. War rhetoric against people is not the methodology, not the sort of communication that came out of the mouth of Jesus or the mouths of any of His followers. In fact, even today, moralists who use war rhetoric will speak of right and wrong, and even some vague and angry god, but never Jesus. Listen closely, and I assure you, they will not talk about Jesus.

In my opinion, if you hate somebody because they are different from you, you’d best get on your knees and repent until you can say you love them, until you have gotten your soul right with Christ.

I can’t say this clearly enough: If we are preaching morality without Christ, and using war rhetoric to communicate a battle mentality, we are fighting on Satan’s side. This battle we are in is a battle against principalities of darkness, not against people who are different from us. In war, you shoot the enemy, not the hostage.

In this way, it isn’t only the moralist looking for a feeling of superiority who commits crimes against God, it is also those of us who react by doing what we want, claiming God’s grace. Neither view of morality connects behavior to a relational exchange with Jesus. When I run a stop sign, for example, I am breaking a law against a system of rules, but if I cheat on my wife, I have broken a law against a person. The first is impersonal; the latter is intensely personal.

* * *

There are a great many motives for morality, but in my mind they are less than noble. Morality for love’s sake, for the sake of God and the sake of others, seems more beautiful to me than morality for morality’s sake, morality to build a better nation here on earth, morality to protect our schools, morality as an identity for one of the parties in the culture, one of the identities in the lifeboat.

I confess, when I was young my mind rebelled form the standard evangelical mantra about morality. My rebellion was reactionary, to be sure. I can’t tell you how many times I have seen an evangelical leader on television talking about this culture war, about how we are being threatened by persons with an immoral agenda, and I can’t tell you how many sermons I have heard in which immoral pop stars or athletes or politicians have been denounced because of their shortcomings. Rarely, however, have I heard any of these ideas connected with the dominant message of Christ, a message of grace and forgiveness and a call to repentance. Rather, the moral message I had heard is often a message of bitterness and anger because OUR morality, OUR culture, is being taken over by people who disregard OUR ethical standards. None of it was connected, relationally, to God at all.

In this way, it has felt like one group in the lifeboat, the moral group, is at odds with another group, the immoral group, and the fight is about dominance in a fallen system rather than rescue from a fallen system. And I wonder, What good does it do to tell somebody to be moral so they can die fifty years later and, apparently, go to hell?

It makes me wonder, and even judge (confession) the motives of somebody who wages a culture war about morality without confessing their own immorality while pointing to the Christ who saved them, the Christ who wishes to rescue everybody.

Morality, in this way, can be a circus act, giving a person a feeling of superiority. And while morality is good, anything we do to get other people to clap, or anything that gives us a more prominent position in a sinking ship, runs the risk of replacing a humble nature pointed at Christ, who is our Redeemer. The biblical idea of morality is behavior associated with our relationship with Jesus, not bait for pride.

In fact, morality as a battle cry against a depraved culture is simply not a New Testament idea. Morality as a ramification of our spiritual union and relationship with Christ, however, is.

Paul said to the church at Rome that those who chose immorality would be given over to a depraved mind and their lives would be ruined, but in the next breath he said that because of his great love for lost people, he would be willing to go to hell and take God’s wrath upon himself. And he said this even about the Jews who were persecuting him. In other words, the call to morality is delivered through a changed and forgiven heart, a heart regenerated and delivered by Christ, desiring that all people repent and come to know Him. There is nothing here we can use in the lifeboat at all. The agenda is all God’s not ours, and God’s agenda is love.

I was thinking of Paul recently when I saw an evangelical leader on CNN talking about gay marriage. The evangelical leader agreed with the apostle Paul about homosexuality being a sin, but when it came time to express the kind of love Paul expressed for the lost, the kind of love that says, I would gladly take God’s wrath upon myself and go to hell for your sake, the evangelical leader sat in silence. Why? How can we say the rules Paul presented are true, but neglect the heart with which he communicated those rules?

My suspicion is the evangelical leader was able to do this because he had taken on the morality of God as an identity with which he was attempting to redeem himself to culture, and perhaps even to God. This is what the Pharisees did, and the same Satan tricks us with the same bait: justification through comparison. It’s an ugly trick, but continues to prove effective.

* * *

I was the guest on a radio show recently that was broadcast on a secular station, one of those conservative shows that paints Democrats as terrorists. The interviewer asked what I thought about the homosexuals who were trying to take over the country. I confess I was taken aback. I hadn’t realized that homosexuals were trying to take over the country.

“Which homosexuals are trying to take over the country?” I asked.

“You know,” the interviewer began, “the ones who want to take over Congress and the Senate.”

I paused for a while. “Well,” I said, “I’ve never met those guys and I don’t know who they are. The only homosexuals I’ve met are very kind people, some of whom have been beat up and spit on and harassed and, in fact, feel threatened by the religious right.”

Think about it. If you watch CNN all day and see extreme Muslims in the Middle East declaring war on America because they see us immoral, and then you read the paper the next day to find the exact same words spoken by evangelical leaders against the culture here in America, you’d be pretty scared. I’ve never heard of a homosexual group trying to take over the world, or for that matter the House or Senate, but I can point you to about fifty evangelical organizations who are trying to do exactly that (emphasis mine). I don’t know why. In my opinion, we should tell people about Jesus, not try to build some kind of temporary moral civilization here on earth. If you want that, move to Salt Lake City.

“And what is the name of this homosexual group that is trying to take over America?” I asked the host, somewhat angry at his ignorant misuse of war rhetoric.

“Well, I hear about them all the time,” he said, rather frustrated with me.

“If you hear about them all the time, what is the name of their organization?”

“Well, I don’t know right now. But they are there.”

“Can I list for you ten or so Christian organizations who are working to try to get more Christians in the House and the Senate?” I said to the host.

“Listen, I get your point,” he said.

“But I don’t think you do. Here is my position: As a Christian, I believe Jesus wants to reach out to people who are lost and, yes, immoral—immoral just like you and I are immoral; and declaring war against them and stirring up your listeners to the point of anger and giving them the feeling that their country, their families, and their lifestyles are being threatened is only hurting what Jesus is trying to do. This isn’t rocket science. If you declare war on somebody, you have to either handcuff them or kill them. That’s the only way to win. But if you want them to be forgiven by Christ, if you want them to live eternally in heaven with Jesus, then you have to love them. The choice is yours and my suspicion is you will be held responsible by God, a Judge who will know your motives. So go ahead and declare war in the name of a conservative agenda, but don’t do it in the name of God. That’s what militant Muslims are doing in the Middle East, and we don’t want that here.”

Amazingly, the host kept me on and allowed me to tell a story or two about interacting with supposed pagans in a compassionate exchange, and later even admitted that his idea that homosexuals were trying to take over the country had originated from an e-mail he had received, an e-mail he had long since thrown away but he thought perhaps from some kind of homosexual organization.

To be honest, I think most Christians, and this guy was definitely a Christian, want to love people and obey God but feel they have to wage a culture war. But this isn’t the case at all. Remember, we are not elbowing for power in the lifeboat. God’s kingdom isn’t here on earth. And I believe you will find Jesus in the hearts of even the most militant Christians, moving them to love people, and it is only their egos, and the voice of Satan, that cause them to demean the lost. What we must do in these instances is listen to our consciences, and allow Scripture to instruct us about morality and methodology, not just morality.

Paul was deceived when he persecuted Christians, thinking he was doing it to serve God, but God went to him, blinded him, and corrected his thinking. After this, Paul loved the people he had previously hated; he began to take the message of forgiveness to Jews and Gentiles, to male and to female, to pagans and prostitutes. At no point does he waste his time lobbying government for a moral agenda. Nobody in Scripture who knew and followed Jesus wasted their time with any of this; they built the church, they love people.

Once Paul switched positions, many people tried to kill him for talking about Jesus, but he never lifted a fist; he never declared war. In fact, in Athens, he was so appreciated by pagans who worshiped false idols, they invited him to speak about Jesus in an open forum. In America, this no longer happens. We are in the margins of society and so we have our own radio stations and television stations and bookstores. Our formulaic, propositional, lifeboat-territorial methodology has crippled the kingdom of God. We can learn a great deal from the apostles. Paul would go so far as to compliment the men of Athens, calling them “spiritual men” and quoting their poetry then telling them the God he knew was better for them, larger, stronger, and more alive than any of the stone idols they bowed down to. And many of the people in the audience followed him and had more questions. This would not have happened if Paul had labeled them as pagans and attacked them.

A moral message, a message of US versus THEM, overflowing in war rhetoric, never hindered the early message of grace, or repentance toward dead works and immorality in exchange for a love relationship with Christ. War rhetoric against people is not the methodology, not the sort of communication that came out of the mouth of Jesus or the mouths of any of His followers. In fact, even today, moralists who use war rhetoric will speak of right and wrong, and even some vague and angry god, but never Jesus. Listen closely, and I assure you, they will not talk about Jesus.

In my opinion, if you hate somebody because they are different from you, you’d best get on your knees and repent until you can say you love them, until you have gotten your soul right with Christ.

I can’t say this clearly enough: If we are preaching morality without Christ, and using war rhetoric to communicate a battle mentality, we are fighting on Satan’s side. This battle we are in is a battle against principalities of darkness, not against people who are different from us. In war, you shoot the enemy, not the hostage.

Monday, March 28, 2005

MARCH BOOK REVIEW: "Searching For God Knows What" by Donald Miller PART I

Nashville, TN: Nelson Books, 2004

I had not planned on reviewing “Searching For God Knows What” so soon. I devoured Donald Miller’s second book after being so affected by his initial foray into literature, “Blue Like Jazz” (see last month’s book review). What I discovered was a book even better than its predecessor and a particular chapter that was as moving, profound, and powerful as nearly anything I have ever read. I have decided to blog the entire chapter (don’t worry, it’s not a long chapter—thank goodness, since I had to type the entire thing out!—and I’ll blog it in pieces throughout the week).

I hope you enjoy and are as challenged by what Miller has to say here as I was. The chapter, entitled, “Morality: Why I Am Better Than You” is a stunning insight into God’s reasons for the rules that govern our lives and the ways in which many of us twist them in order to feel superior to one another. Do we embrace Christian morality because we adore God and want, above all things, to imitate Him, or do we see the Bible as little more than a rule book and morality as a score sheet, clearly delineating us as better Christians who can then wield our supremacy as a weapon against those who don’t measure up? How much damage have Christians done by promoting a religion more interested in being right than in being in right relationship? And in what ways is Christianity intentionally ignorant of the very shortcomings and evils it is so quick to point out in others?

It may strike some as beginning rather slowly. Stick with it throughout the week. There are sections that made my jaw drop. It will probably inspire some comments. I hope it does. I encourage you to engage in the dialogue and share your feelings.

A great concern for those who defend a propositional gospel over a relational gospel is morality. Some feel that if we do not emphasize morality, people will have too much fun and refuse to play by the rules the rest of us who know God have to play by. But I don’t think this is true. I’ve heard it said that Mormonism is the fastest-growing religion and my guess is, the fast growth is because it offers a strict morality, a system of rights and wrongs that people can live by as well as accountability, so they don’t cheat on their spouses or kick their dogs. All of us subscribe to some kind of morality, mostly born of a conscience rather than a book. And the Bible is not structured as a moral code. It does not have all the answers on right and wrong. It has some, enough to guide a man’s conscience, but a book containing a complete moral code would require all pages in all books.

Somehow, and for some reason, each of us subscribes to a kind of morality, and though for some this code is not defined, it is understood and adhered to. Grievances, then, are disagreements in the moral code, not one side holding to “it” and another side disregarding “it,” which, unfortunately, is often an evangelical position.

The truth is, we all want morality. We know morals will make us better people, and we even feel a kind of nobility when we subscribe to and defend a code. I watched a documentary recently about young African-American men in urban New York City who are turning in droves to Islam because of its moral guidance. Each of the young men was looking for a father figure, for a mentor who would provide for him boundaries, understanding intrinsically that life has rules and parameters and to succeed in the soul, one must learn these parameters. Don’t get me wrong, I don’t believe Muhammad was a true prophet, but I enjoyed watching this documentary because it reminded me that I, too, have parameters and rules with which to navigate my existence.

Lately, however, I have been thinking of morality in less conceptual terms, less as a system of rules and regulations and more as a concept very beautiful and alive. Please do not think I am blurring the lines between right and wrong; rather, I am wanting to bring these lines to life to reveal a guide and a judge. The reason I have been feeling this way is not because morality gives us boundaries or because it helps us live clean lives, though morality does these things, but rather because, in some mysterious way, morality pleases God.

One of the great problems with morality for me in the past was that it didn’t seem to be connected to anything. I no longer believe morality will redeem me. What I mean by this is that, often, when I had lustful thoughts, greedy thoughts, and envious thoughts, or for that matter performed lustful actions, actions that stemmed from greed and envy, I felt that I would go to hell for doing them, for thinking these things.

Growing up in a small conservative church in the South, you hear more about morality than you do Christ. If you were immoral, if you danced, or cussed, you were made to feel that God no longer liked you. And if you were moral, you were made to feel not one with Christ, but right and good and better than other people. These things were not stated directly, but the environment left me with this impression. Christian spirituality, then, hinged on whether or not a person behaved.

I don’t mean any of this to suggest I don’t want to behave, or what I want to go on sinning and say that it is okay with God. There is no part of me that believes anything like this can be defended scripturally. A god who says everybody can do as they please would be a bad god, a bad father, giving license for anarchy. Love creates rules and forgives when they are broken. People would hurt themselves and others if they did anything they wanted. People do hurt themselves and others all the time by neglecting laws and rules.

What I really wanted, though, was a reason for morals, a reason stronger than somebody’s simple suggestion that right was right and wrong was wrong.

When David wrote his Twenty-third Psalm he indicated God led him in paths of righteousness for His name’s sake. This struck me, recently, when I was reading through the Psalms. I had always thought morality was something God created exclusively to keep mankind out of the ditches, and to a large degree, I suppose this is true, but David’s concept of morality was quite new to me and I wondered exactly what he meant by the phrase “for His name’s sake.”

Peter would argue in the book of Acts that when David talked about the Lord, he was talking about Jesus, acting as a kind of prophet. And in this light, the Twenty-third Psalm becomes quite beautiful. The Valley of the Shadow of Death, I came to learn while studying this passage, is an actual valley outside Jerusalem. It is treacherous terrain, and shepherds once herded sheep through this valley to move them to green pastures and fresh water. There were crags in the rocks, ditches, and thronbushes that sheep, simple as they are, would fall into, so shepherds had to use their staffs, those big sticks with the rounded hooks on the end, to reach into he crags and ditches to rescue the sheep. And the shepherd also had a rod he would use to scare off wild animals, keeping the sheep safe in the passage. In the Twenty-third Psalm, David says, “Thy rod and thy staff they comfort me.” (v. 4 KJV), and when I think of myself as a sheep, looking up at Jesus, who has a staff to rescue me and a rod to protect me, It makes me feel that this passage is quite endearing, that basically I am a simple sheep, having very little idea of what is right and wrong, and Jesus is going to pull me out of the ditches when I screw up, and protect me from spiritual enemies who, as we’ve already discussed, roam around like lions.

And then the words regarding Christ’s leading us in the paths of righteousness come up and I know David is talking about the safe ground through the Valley of the Shadow of Death, and how there is a right way, a way that is prudent, a way that doesn’t have the crags and bushes; and this is the way of God’s morality, That is, God’s ethics, His conscience instilled in man and guided by Scripture, are the best ways to travel through a fallen world, through the Valley of the Shadow of Death, or what I have referred to as a lifeboat and a circus.

It made me wonder, then, if the idea of morality is just another ramification of the Fall. Paul even says that the law was given to the Jews to show them they couldn’t follow the law, to reveal to them the depravity of their nature, to show them the cancer that lived inside them so they would pay attention to the Doctor.

In my own life, I try to be moral, but I am no good at it. It becomes obvious, in my effort, that I have this cancer Paul alludes to, that I am in this fallen body with a fallen mind and a fallen nature. That said, I don’t suppose we will have any kind of morality in heaven, any thought about right and wrong, once we are with God, once our minds and our bodies and our natures are replenished and healed in His light and His goodness. No, morality exists only because we are fallen, not unlike medicine exists because people get sick.

Morality, then, if you think about it, is the way we imitate God. It is the way we imitate the ways of heaven here on earth. Jesus says, after all, to know Him we must follow Him, we must cling to Him and imitate Him, and many places in Scripture the idea is presented that if we know Him, we will obey Him.

If you look for this relational concept of morality, you see it all through Scripture. Paul connects the idea of morality to Christ in the books of Ephesians and Romans, and the author of Hebrews directly connects morality to our relationship with God in several places in that text. John the Evangelist, in all three of his short books at the end of the Bible, keeps saying that if we know God we will love our brother, and if we know God we will obey.

I was contacted by a magazine editor recently who asked if I would consider writing a few articles for his publication. The editor told me his magazine was unique in that both Christians and people who weren’t Christians contributed, which allowed them to offer a wide variety of perspectives in an open-table format. I thought the magazine sounded terrific and asked him if he would send me a copy. A few days later the magazine arrived, and I took it to Powell’s to sit and read in the coffee shop. I have to tell you, I didn’t like what I read. The first article was a shabbily written diatribe against conventional concepts of morality. The writer said he was in a Christian rock band but didn’t see himself as being any different from any other rock star, saying proudly that he frequently slept with his girlfriend, that he smoked pot and got drunk and applauded anybody who was willing to experiment. He went on to excuse his actions by claiming God’s grace. I read the article a couple of times and realized, perhaps, what it was that David and Paul were speaking of when they connected morality to God’s glory, and immorality to His personal pain.

Can you imagine being a bride in a wedding, walking down the aisle toward your bridegroom, and during the procession, checking out the other groomsmen, wondering when you could sneak off to sleep with one of them, not taking the marriage to your groom seriously? Paul became furious at the church in Corinth for allowing a man to sleep with his stepmother. It makes sense to think of this as Paul’s way of protecting the beauty and grandeur of a union with Christ. In this way, immorality is terrible because it is cheating on the Creator, who loves us and offers Himself as a bridegroom for the bride.

When I said I was looking for a reason for morality, this is what I meant. The motive is love, love of God and of my fellow man.

Sunday, March 13, 2005

NASKIRK

Every year, my church's boy's club, the Royal Rangers (think religious Boy Scouts) puts on a pinewood derby. Last year's was so successful and enjoyable that the church opened the races up to anyone who wished to participate.

Struck with inspiration, I entered the Star Trek: Original Series shuttlecraft, Galileo Seven for this year's race which took place yesterday.

Unfortunately, this is how my car performed for the majority of the heats:

But fortune favors the bold and what I couldn't win in speed, I won in style--First Place in Show!

"I'd like to thank all the little people in red uniforms who died horrible deaths so I could be here today..."

Struck with inspiration, I entered the Star Trek: Original Series shuttlecraft, Galileo Seven for this year's race which took place yesterday.

Unfortunately, this is how my car performed for the majority of the heats:

But fortune favors the bold and what I couldn't win in speed, I won in style--First Place in Show!

"I'd like to thank all the little people in red uniforms who died horrible deaths so I could be here today..."

Tuesday, March 08, 2005

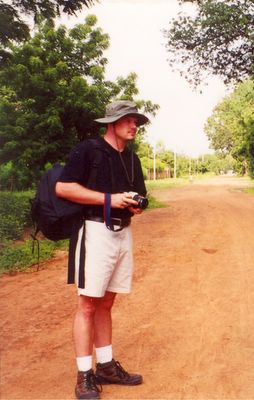

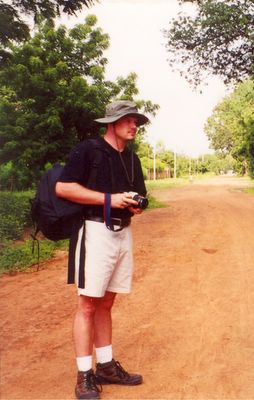

Splendor and Squalor: PART III

Growing up in Colorado, I was always surrounded by the images of exotic lands far away. Downstairs in our family room, my mother had labored for months over a series of immense collages illustrating the many countries she had had the opportunity to visit while going to or from the mission field. I used to stand in that room and soak in every image—the towering Swiss Alps, Big Ben on a rainy English afternoon, the Eiffel tower seen from the river Seine, windmills spinning lazily amid Dutch tulips… For me, these collages represented some of the most marvelous pieces of earth the world had to offer. They also represented places I never dreamed I would have the opportunity to see with my own eyes.

It has been three years since I moved to Europe and I have seen 20 countries and counting. I have seen the mighty Coliseum, the bullrings of Spain, the castles of Prague. I have intimately witnessed each and every one of the countries those posters of my childhood represented, and more.

And yet, in that room of my old house, there was a very special corner with multiple posters devoted wholly to the one location more exotic and untouchable than any other—Africa. True, I had made it to Europe, but surely Africa was beyond my reach. And yet, here I was.

When I first realized that Africa was going to be a reality, my naïve western mind was aflutter with the possibilities of what I was going to see, taste, and hear. I pictured vast plains carpeted with undulating waves of wild beasts; lions roaming baobab-shaded forests, and crocodiles slinking into brown rivers while giant pythons watched from positions high in the trees.

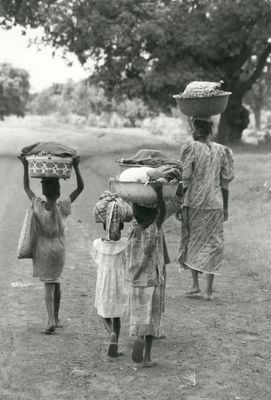

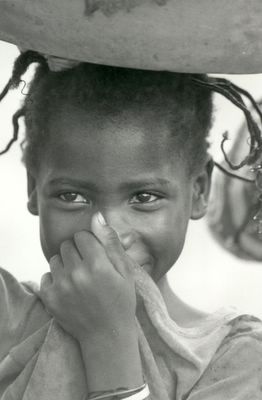

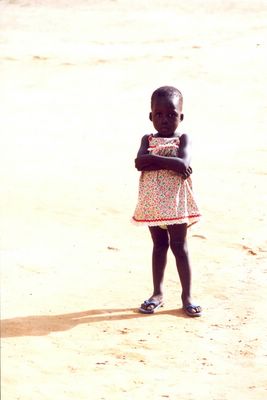

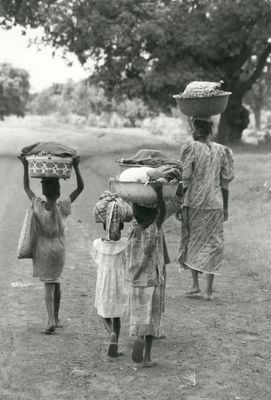

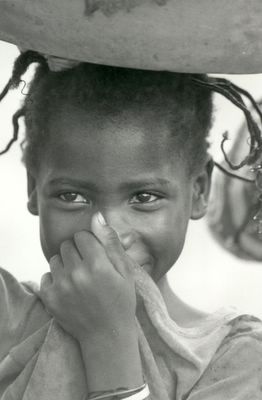

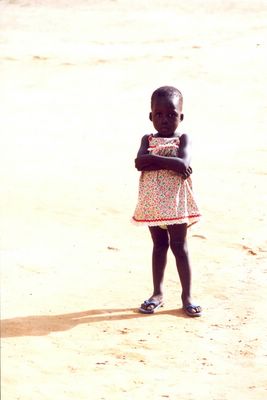

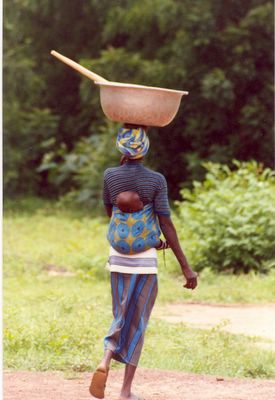

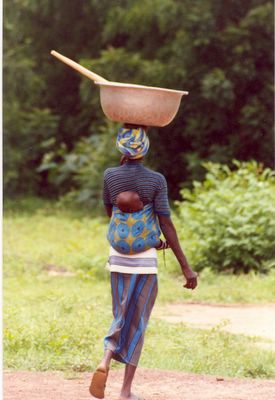

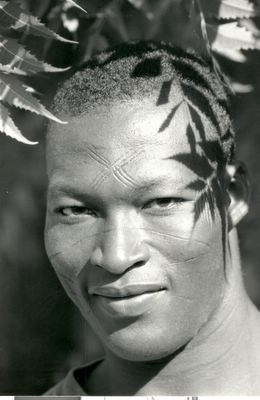

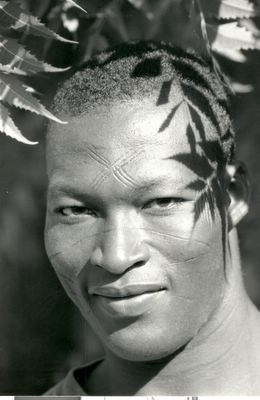

But the truth of the matter is that none of that is Africa. Not truly. I could have gone the entire vacation without seeing one wild animal and I would have still boarded the plane for home having seen a multitude more than any tourist ever could. I knew I had already seen the real Africa—I had seen it in the face of Esther, heard it in the voice of Benjamin, felt it in the arms of Tingandi—the real Africa was her people. I had tasted some incredible delicacies in Burkina—from the tart bite of weta, the smooth chalk of tama, the sugary syrupiness of mangos, the sweetness of roasted corn—but none was more satisfying or more delicious than her people.

For me, Africa will always be the smiling faces of her children as seen through the lens of my camera.

And there are many such faces. According to Nancy Valnes, a missionary whose gospel is by necessity more contraceptives than Christianity, Burkina has the second highest death toll to AIDS in West Africa. In some of the more urban areas, orphaned children are out-populating their adult counterparts. But as the song goes, “they are all precious in His sight.” Mine too.

I will always be able to instantly recall chasing the more daring children around the village huts or how the smaller ones shrieked in terror at the strange white man who approached them.

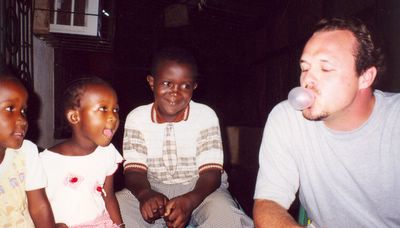

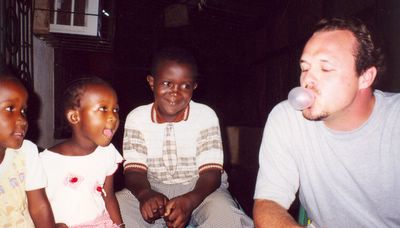

I will never forget the looks they made as I handed out Jolly Ranchers or Bazooka Joe bubble gum, or befuddled them with something they had never seen before—a balloon.

I will always remember driving down the road and waving to the children working in the fields and watching them drop their hoes to sprint, giggling after the truck. I easily took twice as many pictures of Africa’s little ones as I did the castles and cathedrals of France where I had been vacationing before this trip began.

As I followed my grandparents and mother around to all the tiny villages, tucked away like so many forgotten gems in the bush, I discovered exactly why they had fallen in love with Africa and more importantly fallen in love with her lifeblood. And now, all those stories I had heard growing up have become personal and intimate memories of my own. I have seen first hand where the panther killed my mother’s pet rabbits and set down bloody paw prints as it moved throughout the inside of their house that hot summer night while they slept; I have seen where my mother used to rise before the sun and ride her horse at breakneck speeds before being called in for home school; I have seen where my grandfather brought down the mad hippo with one shot; where the scorpion scaled my uncle’s bicycle wheel, unfazed whatsoever by its crushing rotation. All these stories and more are now a part of my life too, a collective set of memories we all share. There was always a part of my family I could never truly understand, an inner sanctum to which I could not hope to gain access no matter how hard I tried. I could not comprehend my grandparent’s quest in life nor my mother’s overwhelming upbringing until I physically set foot on the sacred soil that is Africa and saw things through their eyes.

My mother has never really considered herself an American. She has always said that she is a Burnkinaba “waiting for her black paint.” While on this trip, someone honored her by calling her a “Daughter of Africa.” If true, and I know now that it is, than I guess that makes me a grandchild of Africa. I cannot think of a greater honor, nor a greater family into which I’ve been adopted.

* * *

12:30pm

Nazinga Game Ranch

Burkina Faso, West Africa

Our Land Cruiser is heavier by one.

Having returned to the camp for a late breakfast, we’re now leaving with a local African guide who perches himself deftly on the front of the luggage rack, legs nearly dangling over the windshield. While we grip the metal for dear life, he sits calmly with his hands folded in his lap, perfectly balanced.

“He says he knows where the elephants are,” Clark says, wrenching open his door. Sliding back into the passenger seat he says to no one in particular, “which may mean nothing at all.”

The morning was not a total loss. Though the rain continued unabated for hours, it was only the first hour or so in which it fell in sufficient measure to keep us cocooned inside our SUV. The remainder of the morning it slowed to a heavy drizzle and allowed us the opportunity to stick our heads from the half open windows and scan the bush. By the time we returned to camp for some much needed breakfast, the coffee long since having borne acidic craters in our stomachs, we had seen numerous species of antelope, hartebeest, and even warthog. But still, no sign of any elephant.

A few green oranges and some jam-lathered French bread later, we are at it again. There is a renewed hope among us that this time out may be the one, although none of us are sure if that isn’t just our contented bellies speaking. Very few minutes into the trek we realize our guide has eyes to match the hawks and vultures we see constantly circling overhead. Pointing out a crocodile sunning himself on a pond log, it takes the rest of us a full minute to see what he is referring to. Emboldened by his keen eyesight, we settle back into our ridged metal pallet.

But Africa is not cooperating. Worse still, she is mocking us. From atop our precarious platform we can see deep impressions made in the sodden dirt, impressions that look suspiciously like elephant tracks. A bit further up a heaping pile of dung lies beside the remains of a tree snapped at its base by something large moving through the bush. Elephants certainly passed though here…but when? We watch our guide’s face almost as much as the tree line, hoping to see some flash of recognition there. It does not come.

It has been several hours now and we are no closer to our objective then when we rose this morning. Adding insult to injury, the lighthearted joking about the state of our backsides has now converted into full-fledged complaining. Every hole in the road is a groan, every large rock a grimace. Pain comes not only from below but from above as well. Low hanging branches frequently catch the unvigilant off guard and leave him or her with a stinging welt and a mouthful of leaves. Like contortionists, we attempt to rearrange our bodies in unnatural angles—anything to relieve surface area contact.

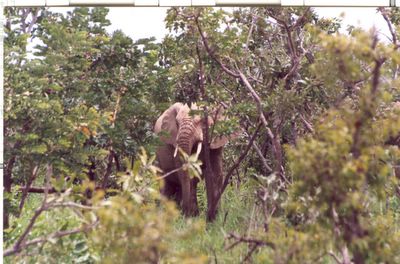

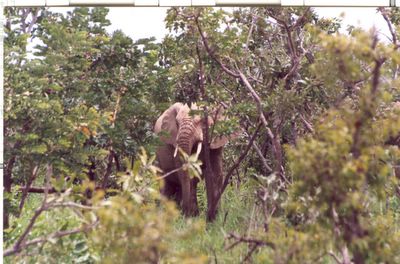

I scratch absentmindedly at a plethora of swollen mounds on my legs. Malaria inception point number one…number two…number three… There is talk of returning to camp and taking some lunch and some much needed rest when our guide’s arm flies out, pointing to the left of us. He quietly but effectively mouths the word, “Elephant.” Where!? The SUV rumbles to a stop and six sets of eyes attempt to follow our guide’s outstretched arm into the bush. All we can see are trees, trees, and more trees. As catlike as possible, we slide from the edge of our roost and cup hands over our eyes and peer intently.

And then we see them. Something immensely large and gray is moving behind a veil of foliage. Its steps are deliberate and plodding, the motions of a titanic behemoth perfectly secure with its place in the world, afraid of nothing. Through a break in the trees, three elephants--two adults and a juvenile--become visible. They are magnificent, in a way that is almost otherworldly. They lumber from the trees, picking at branches with their mighty trunks while I creep as close as the guide will dare.

A horde of sweat bees, thick as a mesh, swarm around my face and arms, drawing drops of blood at dozens of bite marks. Ignoring them, I snap a roll of film. If anyone could have seen through the shroud of bugs around my face, they would have seen a smile that stretched from ear to ear.

It has been three years since I moved to Europe and I have seen 20 countries and counting. I have seen the mighty Coliseum, the bullrings of Spain, the castles of Prague. I have intimately witnessed each and every one of the countries those posters of my childhood represented, and more.

And yet, in that room of my old house, there was a very special corner with multiple posters devoted wholly to the one location more exotic and untouchable than any other—Africa. True, I had made it to Europe, but surely Africa was beyond my reach. And yet, here I was.

When I first realized that Africa was going to be a reality, my naïve western mind was aflutter with the possibilities of what I was going to see, taste, and hear. I pictured vast plains carpeted with undulating waves of wild beasts; lions roaming baobab-shaded forests, and crocodiles slinking into brown rivers while giant pythons watched from positions high in the trees.

But the truth of the matter is that none of that is Africa. Not truly. I could have gone the entire vacation without seeing one wild animal and I would have still boarded the plane for home having seen a multitude more than any tourist ever could. I knew I had already seen the real Africa—I had seen it in the face of Esther, heard it in the voice of Benjamin, felt it in the arms of Tingandi—the real Africa was her people. I had tasted some incredible delicacies in Burkina—from the tart bite of weta, the smooth chalk of tama, the sugary syrupiness of mangos, the sweetness of roasted corn—but none was more satisfying or more delicious than her people.

For me, Africa will always be the smiling faces of her children as seen through the lens of my camera.

And there are many such faces. According to Nancy Valnes, a missionary whose gospel is by necessity more contraceptives than Christianity, Burkina has the second highest death toll to AIDS in West Africa. In some of the more urban areas, orphaned children are out-populating their adult counterparts. But as the song goes, “they are all precious in His sight.” Mine too.

I will always be able to instantly recall chasing the more daring children around the village huts or how the smaller ones shrieked in terror at the strange white man who approached them.

I will never forget the looks they made as I handed out Jolly Ranchers or Bazooka Joe bubble gum, or befuddled them with something they had never seen before—a balloon.

I will always remember driving down the road and waving to the children working in the fields and watching them drop their hoes to sprint, giggling after the truck. I easily took twice as many pictures of Africa’s little ones as I did the castles and cathedrals of France where I had been vacationing before this trip began.

As I followed my grandparents and mother around to all the tiny villages, tucked away like so many forgotten gems in the bush, I discovered exactly why they had fallen in love with Africa and more importantly fallen in love with her lifeblood. And now, all those stories I had heard growing up have become personal and intimate memories of my own. I have seen first hand where the panther killed my mother’s pet rabbits and set down bloody paw prints as it moved throughout the inside of their house that hot summer night while they slept; I have seen where my mother used to rise before the sun and ride her horse at breakneck speeds before being called in for home school; I have seen where my grandfather brought down the mad hippo with one shot; where the scorpion scaled my uncle’s bicycle wheel, unfazed whatsoever by its crushing rotation. All these stories and more are now a part of my life too, a collective set of memories we all share. There was always a part of my family I could never truly understand, an inner sanctum to which I could not hope to gain access no matter how hard I tried. I could not comprehend my grandparent’s quest in life nor my mother’s overwhelming upbringing until I physically set foot on the sacred soil that is Africa and saw things through their eyes.

My mother has never really considered herself an American. She has always said that she is a Burnkinaba “waiting for her black paint.” While on this trip, someone honored her by calling her a “Daughter of Africa.” If true, and I know now that it is, than I guess that makes me a grandchild of Africa. I cannot think of a greater honor, nor a greater family into which I’ve been adopted.

* * *

12:30pm

Nazinga Game Ranch

Burkina Faso, West Africa

Our Land Cruiser is heavier by one.

Having returned to the camp for a late breakfast, we’re now leaving with a local African guide who perches himself deftly on the front of the luggage rack, legs nearly dangling over the windshield. While we grip the metal for dear life, he sits calmly with his hands folded in his lap, perfectly balanced.

“He says he knows where the elephants are,” Clark says, wrenching open his door. Sliding back into the passenger seat he says to no one in particular, “which may mean nothing at all.”

The morning was not a total loss. Though the rain continued unabated for hours, it was only the first hour or so in which it fell in sufficient measure to keep us cocooned inside our SUV. The remainder of the morning it slowed to a heavy drizzle and allowed us the opportunity to stick our heads from the half open windows and scan the bush. By the time we returned to camp for some much needed breakfast, the coffee long since having borne acidic craters in our stomachs, we had seen numerous species of antelope, hartebeest, and even warthog. But still, no sign of any elephant.

A few green oranges and some jam-lathered French bread later, we are at it again. There is a renewed hope among us that this time out may be the one, although none of us are sure if that isn’t just our contented bellies speaking. Very few minutes into the trek we realize our guide has eyes to match the hawks and vultures we see constantly circling overhead. Pointing out a crocodile sunning himself on a pond log, it takes the rest of us a full minute to see what he is referring to. Emboldened by his keen eyesight, we settle back into our ridged metal pallet.

But Africa is not cooperating. Worse still, she is mocking us. From atop our precarious platform we can see deep impressions made in the sodden dirt, impressions that look suspiciously like elephant tracks. A bit further up a heaping pile of dung lies beside the remains of a tree snapped at its base by something large moving through the bush. Elephants certainly passed though here…but when? We watch our guide’s face almost as much as the tree line, hoping to see some flash of recognition there. It does not come.

It has been several hours now and we are no closer to our objective then when we rose this morning. Adding insult to injury, the lighthearted joking about the state of our backsides has now converted into full-fledged complaining. Every hole in the road is a groan, every large rock a grimace. Pain comes not only from below but from above as well. Low hanging branches frequently catch the unvigilant off guard and leave him or her with a stinging welt and a mouthful of leaves. Like contortionists, we attempt to rearrange our bodies in unnatural angles—anything to relieve surface area contact.

I scratch absentmindedly at a plethora of swollen mounds on my legs. Malaria inception point number one…number two…number three… There is talk of returning to camp and taking some lunch and some much needed rest when our guide’s arm flies out, pointing to the left of us. He quietly but effectively mouths the word, “Elephant.” Where!? The SUV rumbles to a stop and six sets of eyes attempt to follow our guide’s outstretched arm into the bush. All we can see are trees, trees, and more trees. As catlike as possible, we slide from the edge of our roost and cup hands over our eyes and peer intently.

And then we see them. Something immensely large and gray is moving behind a veil of foliage. Its steps are deliberate and plodding, the motions of a titanic behemoth perfectly secure with its place in the world, afraid of nothing. Through a break in the trees, three elephants--two adults and a juvenile--become visible. They are magnificent, in a way that is almost otherworldly. They lumber from the trees, picking at branches with their mighty trunks while I creep as close as the guide will dare.

A horde of sweat bees, thick as a mesh, swarm around my face and arms, drawing drops of blood at dozens of bite marks. Ignoring them, I snap a roll of film. If anyone could have seen through the shroud of bugs around my face, they would have seen a smile that stretched from ear to ear.

Splendor and Squalor: PART II

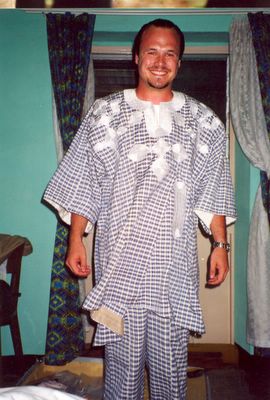

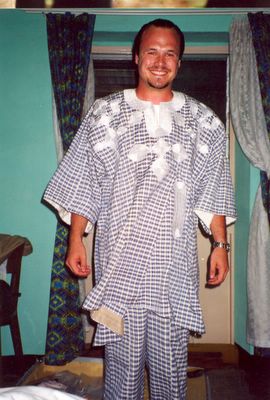

Our stay in Africa was to be divided in two nearly equal halves. These parts, mirroring my family’s history in Burkina, would place us for the first week in the village of Boromo, after which time we would return to Ouaga for the latter half of our trip. When my grandparents set out for the mission field, they first went to Paris for a year to learn French. The next stop was to Ouagadougou where they started over again and for the next year, learned the local dialect of More (pronounced “Moore-eh”). But Ouagadougou was not to be their home. Their home for almost the next decade would be several hours to the southwest in the medium-sized village of Boromo.

Traveling to Boromo was nothing like it was when my grandparents lived here. They relate stories of a half-day of travel on a wide dirt road, chocking on the red dirt that coated every surface of thier car, clothes and bodies. Our trip today takes barely over two hours and is sped along by a newly installed paved road that finds my grandparents shaking their heads in astonishment. The ground here is a bright red contrasted sharply with the thick green of the vegetation that flashes past our car in dense emerald smudges. This is the rainy season and the face Burkina is showing the world is an utterly deceptive one to those who do not understand the African climate. Mere months from now this green will be a distant memory, as will the leaves and foliage that clothe every tree. With unbearably stifling temperatures, the water of the rainy season will evaporate into the burnt browns of the dry season and the African bush will put on the face of a thing more dead than alive. I, for one, am glad I came when I did.

Memories, poignant and as starkly defined as burnished marble flit about my family like so many invisible butterflies as we pull up to the house my grandfather built and in which they raised their children. I find myself snapping pictures of them like some sort of insensitive photojournalist, capturing the moments when they cross the thresholds of the various rooms and the tears soak through and overwhelm them. There will be many tears in the next few days as we amble along the old paths and ingest sights not seen or perhaps even thought of in three decades.

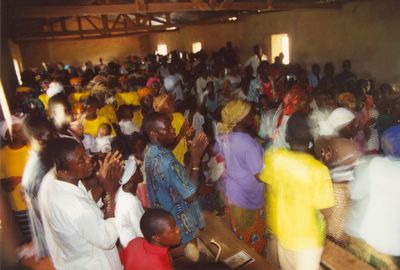

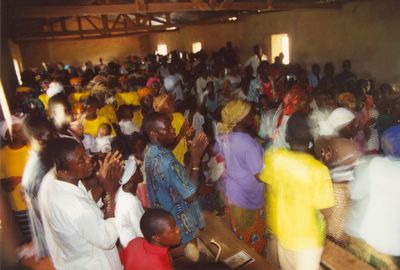

* * *

A parade of people. This is the only possible way to describe the wave upon wave of visitors that came to greet my grandparents and mother. Every day, from shortly after sunrise, to well after dark, a steady stream of visitors fed its way into the house like a human tributary. There are very few private moments on this trip and even fewer to catch one's breath. The people come from near and far, staying for only a few moments or for several days. But they all come with one intent—to fall on the neck of “Papa” and “Madam” and “little Charlene,” to kiss and hold them and let their tears mingle as their lives once did. Pastors and bible-school graduates, old cooks, drivers and groundskeepers, masons and iron-workers, church layman and government officials, Christian and Muslim--they all come.

I watch this with the odd perspective of a well-informed fly on the wall. My grandparents seem charged with electricity and more in their element than I have ever seen them before. It is strangely disconcerting and equally compelling to watch your family chatter way in a language far more foreign than any taught on western campuses and one in which I have only heard when there was a need to secretly converse about that year’s Christmas presents. “Don’t you know,” I am told later, “they speak More in heaven!”

The visitors to the house (still in use by French missionaries now in Paris for medical furlough) are a marvelously beautiful bunch. There is no smile in the world at all more beautiful than that made when pearly white teeth break open on deep, black African skin. Tribal scars line and swirl their faces. Melodic voices resonate through teeth chiseled to fine points. The women move with a deliberate and graceful poise. It is of little surprise they can walk (and even ride) with such large bundles atop their heads. The children bear a subservience to their elders that is equal parts refreshing and maddening. They embrace us, covering us with a multitude of kisses and grasp our hands repeatedly while simultaneously chirping contentedly. Their face, beaming, cannot hide the joy of the Lord.

“My heart is full.” One visitor exclaims.

“Not as full as ours,” my grandmother replies.

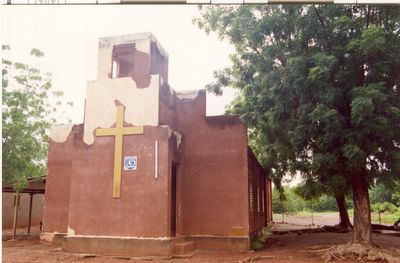

That Sunday, sitting in the church my grandfather constructed and ministered in, we are treated to a service that lasts over five hours. With the sounds of African drums and voices still ringing in our ears, I discover first-hand just how loved my grandparents really are. Packed to capacity, the crowds line the outside of the church, faces peering intently through the slated windows for any glimpse inside.

Eloquent tributes (“They loved us with their hearts, not just their teeth”) and lavish gifts are presented and when my grandmother stands to address the gathering, it is with a broken voice that she announces, “Today, I have tasted heaven.”

Later in the trip, after a similar evening, my grandfather sits silently in the restroom for a long time. When my grandmother asks him through the door if he’s ok, he replies, “I’m just in here bursting my buttons. I’ve never felt so much honor and reverence in my life.”

“Your grandfather always stands up so much straighter here.” My grandmother confides to me afterwards.

* * *

I love the sound of my grandfather’s voice. He has a James Earl Jones quality which, what it lacks is depth of tone, it matches in power and inflection. Be I boy or man, there are few better moments I have experienced than sitting at my grandparent's Portland breakfast table, full on homemade toast and jelly, listening to my grandfather read devotions.

Nearly 80, hunched with time and plagued by pain in his hands, hips and knees, my grandfather is no longer the man I see in the old slides of Africa he loves to pull from the attic every Christmas visit. He cannot move as fast or stand as straight, but I realize a hundred times over, as I stand beside him, taller by nearly two feet, that my grandfather is a giant of a man.

Listening to my grandfather preach several times this trip, I am painfully reminded that it may be one of my last times to be so honored. I smile to myself as he confuses the languages of his sermon, vacillating between English, More and French without noticing he’s made the switch. If a grandson can be more proud of his grandparents than I am, I cannot see how. They are too humble to swell with the pride I allowed myself to be infused with on this trip. Watching my grandparents together (she is ramrod straight, walks more briskly than any 18-year-old, and seems in every way a polar opposite of her husband) I was daily overcome with the realization that my grandparents are truly great human beings who have done truly great things in this world. I could never have comprehended to what degree that was true had I not “tagged along” on this trip.

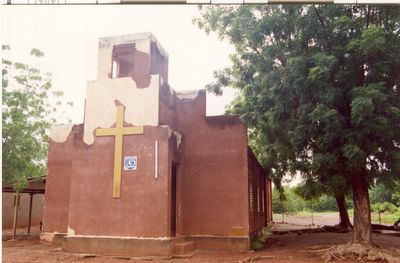

Using Boromo as our base camp of sorts, we journeyed daily to numerous villages that lay in the outlying provinces. Villages with names like Oury, Pompoi, and Bagesi. In each, hundreds of people swarmed from their huts and houses to greet us as we pulled up to the local church building. My grandfather had built nearly every one. The small blue plaque above each entryway denoting the church as of the “Assemblees de Dieu” had become so very familiar that it prompted one person to comment that the three things you see most in Burkina these days are “Blue jeans, Coke-a-Cola, and Assemblies of God churches.”

Nearly every church is packed to overflowing. At many villages, larger buildings are being constructed a stone's throw away. At Ouhabo, we visit with the local congregation as they toil under the hot sun. Half naked women slap mixtures of mud and tar over sun-dried mud bricks and smear it flat. Behind them, several men stomp in a pit of muck, preparing the next batch. The roof is the only thing they cannot provide. The rains make anything other than a metal roof impossible and such materials are nearly unattainable or unfeaisibly expensive. They build the church anyway, confidant that God will provide.